Introduction

Resources

Ideas

Agile approach to research, with many small projects (POC), check up every 3-6 months, which can be integrated into larger projects. All with a general topic, one of the following:

- Ensamble of models which output the certainty of their prediction, instead of the prediction

- Tool for long range prediction (years) with CMIP data

-

Tool for socio-economic decision making with climate data (IPCC report)

- Multi-modal forecaster using both climate and socio-economic data (ex. average income...)

- Graph compression with GNNs, which can be used for data elaboration

-

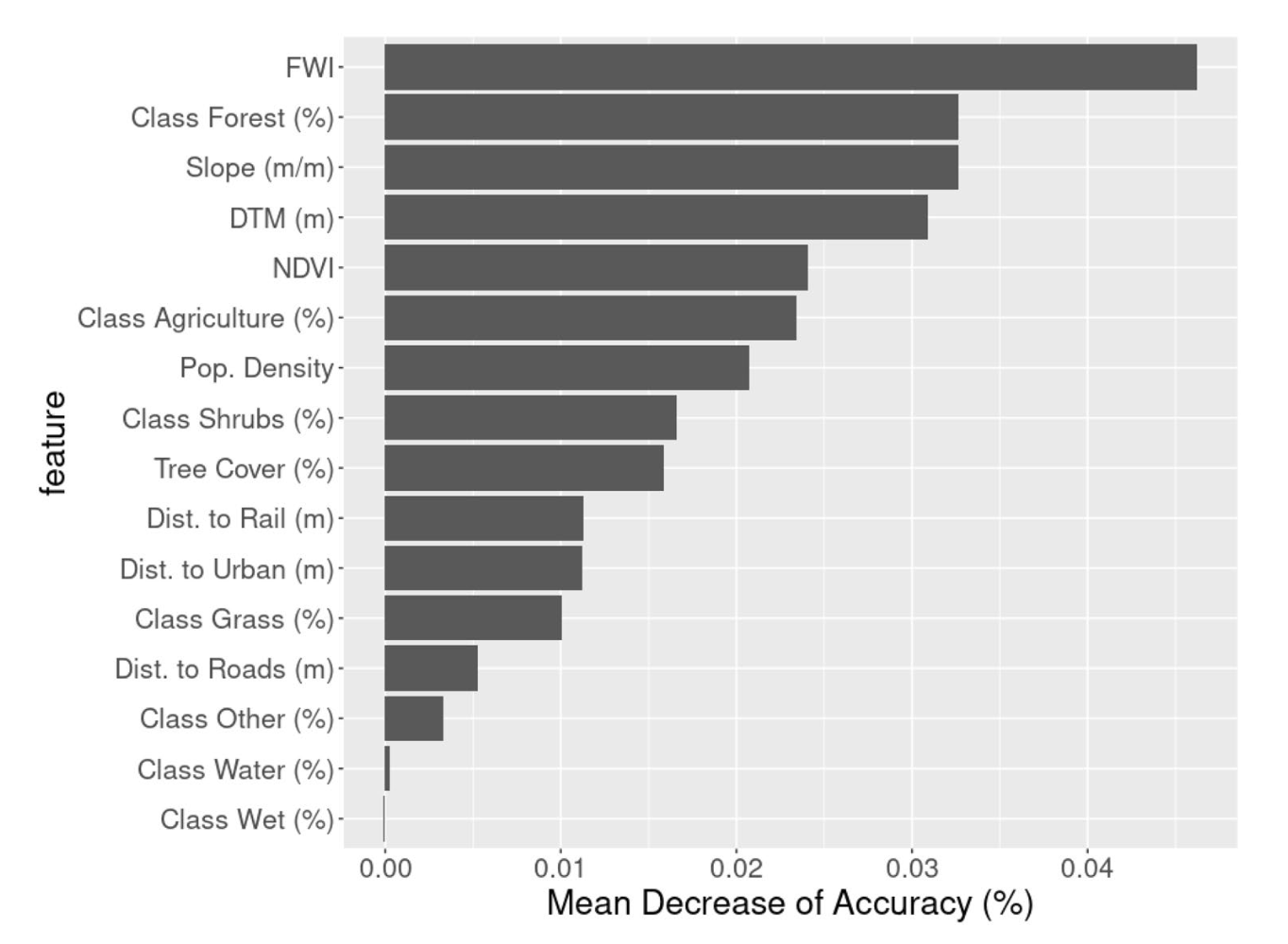

Wildfire prediction/forecasting (with geo)

- Drought prediction/forecasting (with geo)

- add wind data and see expansion

- add temperature data and see expansion

- terrain type (forest, grassland, desert, crops, etc.)

- could help type of crop decisions

- US: (https://www.usgs.gov/news/data-release-combined-wildfire-datasets-united-states-and-certain-territories-1878-2019)

-

Flood prediction/forecasting (with geo)

- Landslide prediction/forecasting (with geo)

- type of terrain (rock, sand, etc.)

- faglie

-

Earthquake prediction/forecasting (with geo)

- Tsunami prediction/forecasting (with geo)

- Volcano prediction/forecasting (with geo)

Useful Datasets

- World Input-Output Database (WIOD)

- Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP)

- World Bank Open Data

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

- Global Burden of Disease (GBD)

- Internal monetary fund (IMF)

Conferences and Links

https://www.climatechange.ai/events/iclr2024

https://deepmind.google/discover/blog/using-ai-to-fight-climate-change/

Research Methodoloogies Course

Research:

- Originality: do not reuse results from others;

- Systematic:

- Rigorous: if you really have to, use others work in a precise way;

- Significant: contribute to knowledge;

Originality

This includes new findings / theorems / laws, new ways of thinking (survey papers), new ways of achieving facts / doing things.

Rigoorous

Integrity, robustness, reproducibility, transparency and precision. Experiments are conducted in a precise way (ex. data collection).

Sapiens - A brief history of humankind.pdf

Research Paradigms

- Formal research: theories, models, proofs

- analytical research: direct / indirect observation

- constructive research: new processes and products

Method: set of principles, rules, and procedures which can guide a person to something

- Does the scientific method exist?

- Are results truth?

- Does the truth hold only in a certain context?

- Is it valid only under certain conditions? Or with a certain level of confidence?

A proof is truth until you manage to disprove it. (confirm is different from prove) One sample is enough to invalidate a theory.

Validation through experimentation, so proof by counter-example

Experimental Method

-

Inductive step: build theory (hypothesis and thesis (generalization))

-

Deductive step: challenge the theory to give it strength

-

Refutation: disproof (could be useful for improvement of the theory)

-

Theory inference: thesis are expressed with levels of certainty (ex. 95% confidence)

-

Sound theory: if whatever it infers is true (does not explain false negatives)

-

Complete theory: if all truths can be inferred / explained (but also non-true facts)

We ideally want a theory to be sound and complete.

Truths can be:

- Quantitative: explain with a certain probability the truth

- Qualitative: explain the truth in a binary way

Case study:

- Observational: novel approaches

- Feasibility: if solution has potential

- Comparative: compare different approaches

- Community: benchmarking

- Replicability: same experiments but different settings

Product of Research

Either enriches the knowledge or usable to further enhance practice. Needs to be usable and diffusable. Results need to be: original (novel), rigorous (mathematical / experimental), significant (have impact / influence).

Publication:

- Incremental work (revisions and refinements)

- Direct diffusion or diffusion after peer review

- Clarification of what you have done

Diffusion techniques:

- Conferences: lower acceptance rate, faster diffusion (easier to publish), have more predictability (fixed submission dates)

- Journals: higher acceptance rate, slower diffusion (harder to publish), have less predictability (rolling submission), more feedback than conferences

Different research communities have different diffusion techniques and habits.

Research Conduct

Research integrity is adherence to ethics principles (open, plagiarism, honest, fair).

Misconduct:

- Fabrication: making up data

- Falsification: manipulating data and research material

- Plagiarism: using others work without proper citation

- Overselling: overestimating the results (making them look better)

Material sent to reviewers is confidential (also do not share label).

- Double blind: anonymity of authors and reviewers

- Single blind: anonymity of reviewers

- No blind: no anonymity (favours taking responsibility)

Seminar Research Methodologies 1 (Research Output and Publication)

In computer science, conference proceedings make up 60% of the research output. Old conferences are better, as more interactive in counseling.

Papers can be retracted (un-published) if they are found to be fraudulent.

WikiCFP (to find conferences)

Time of submission to conferences is usually 6-9 months before the conference date. And 3-6 months to write the first draft of the paper. To understand where to publish, check where similar papers got published (conferences), so you know where they could be accepted.

Books

Complete scholarly topic on one subject. Collection of papers (re-elaborated).

Impact of your publication: how to select?

- Impact factor: number of citations for articles in prev. 2 years divided by the number of articles published in the same period.

Why only in two years? Because it is the time frame in medicine where research tends to lose its relevance. In CS, after 10 years, it is estimated that the paper would have received half of its citations (so it will receive less impact factor). Impact factor is discipline dependant.

Other metrics:

- Scopus: number of citations

- H-index: number of papers with at least h citations.

Ithenticate (to check for plagiarism)

Seminar Research Methodologies 2 (Legal Management of Research)

Can I take my own paper published and host it for freeon my website? No

Data:

- Raw: non-elaborated data (uncertain legal status)

- Processed: elaborated data (certain legal status)

- Different classification of data: legal / personal / anonymous / pseudonymous / confidential.

Copyright protects the expression of ideas, not the ideas themselves. (ex. source code is protected, as its the expression of the idea, but the idea itself is not protected)

Contracts:

- NDA: Non-Disclosure Agreement

- Data Transfer Agreement:

- Licence of IPR: keep ownership of the IPR, but allow others to use it

- Creative Commons:

- Non Commercial: can't use the work for commercial purposes

- Share Alike: if you modify the work, you have to share it under the same license

- No Derivatives: can't modify the work

- Attribution: give credit to the author

University founding not from state, and research not giving profit back to the state, but to the university.

Research Methodologies Extras

Impact: can be potential impact (valued by reviewers and journals and conferences) or real impact (which can be measured only after some time).

How to estimate impact?

Can we use one number metrics?

- Number of citations: (bibliometric) papers with high number of citations are considered to have high impact.

Is there a rationale behind how people cite? Is it uniform? No, it is very variable and depends on the field (different disciplines have different number of average citations). It is also prone to un-ethical practices (self-citations, citation rings, etc) for inflation. Also, the number of citations grows over time and then slows down, and citations may not always be positive (negative citations).

Number of citations is used to calculate the impact factor of journals (reputation of the publisher), which causes highly skewed distributions, with a few papers having a lot of citations and most papers having very few (average is often misleading).

-

H-index: (bibliometric) maximum H such that a given author has published H papers that have each been cited at least H times (goodness of the author). Should not be used for ranking, especially inter-disciplinary, for the reasons above.

-

Number of downloads per artifact: (altmetric) number of times a paper has been downloaded.

-

Number of licences: (altmetric) number of times a paper has been licensed.

Moral: don't use one number metrics for determining the impact of papers or authors.

iCST: conference ranking (list of conferences and their ranking).

GNN Transformers

Introduction

A graph is a kind of data structure, which is composed of nodes (objects) and edges (relationships).

Most of the current GNNs are based on the message passing paradigm, which is a generalization of the convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to non-Euclidean domains.

Often GNNs suffer from the following problems:

- Over-smoothing: the information from the nodes is averaged out, and the model cannot distinguish between nodes that are far away from each other.

- Over-squashing: due to the exponential computation with the increase in model depth.

Use of GNNs in Transformers

There have been developed three main ways to use GNNs in Transformers:

- Auxiliary Modules: GNNs are used to inject auxiliary information to improve the performance of the Transformer.

- Improve Positional Embedding with Graph: compress the graph structure into positional embedding vectors, and input them to the Vanilla Transformer.

- Improve attention matrix from graph: inject graph priors into the attention computation via graph bias terms.

These type of modifications tend to yield improved performance both on node level and graph leevel tasks, more efficient training and inference, and better generalization. This being said different group models enjoy different benefits.

Graph building blocks can be used on top of existing attention mechanisms, can be alternated with self-attention layers, or can be used in conjunction (concatenated) with existing transformer blocks.

Some Architectures

- GraphTrans: adds a transformer sub-networkon top of a standard GNN layer. It performs as a specialized architecture to learn local representation, while the transformer sub-network learns global representation of pairwise node interactions.

- Grover: uses two GTransformers to learn node and edge representations, respectively. The node representations are then used to update the edge representations, and vice versa. The inputs are first passed to a GNN which is trained to extract vectors as query, key and value. This layer is then followed by a self-attention layer.

- GraphiT: adopts a Graph Convolutional Kernel Network layer to produce a stucture aware embedding of the graph. The output of this layer is then passed to a self-attention layer.

- Mesh Graphormer: stacks Graph residual blocks on a multi-head self-attention layer. The graph residual block is composed of a graph attention layer and a graph feed-forward layer. It improves the local interactions using a graph convolutional layer in each transformer block.

- GraphBERT: uses graph residual terms in each attention layer. It concatenates the graph residual terms with the original attention matrix, and then applies a linear transformation to the concatenated matrix.

Positional Embeddings

It is also possible to compress the grqph structure into positional embedding vectors, and input them to the Vanilla Transformer. Some approaches adopt Laplacian eigenvectors as positional embeddings, while others use svd vector of adjacent matrices as positional embeddings.

ViTs

General Circulation Models

Introduction

General Circulation Models (GCMs) are a class of models which use a combination of numerical solvers and tuned representations for small scale processes.

Neural GCM

Neural GCM is a GCM which uses a neural network to represent the small scale processes. It is competitive with ML models on 10 days forecasts, and competitive with IFS on 15 days forecasts.

Uses a fully differentiable hybrid GCM of the atmosphere, with a model split into two main subcomponents:

- A Differentiable Dynamical Core (DDC) which solves the equations of motion (dynamic equations);

- A Learned Physics module, which learns to parametrize a set of physical processes (physics equations) with a neural network.

End-to-end training of GCMs

Uses extended backpropagation between the DDC and the Learned Physics module.

Three loss functions:

- MSE for accuracy: Takes into account the layer lead time over the forecast horizon. Double penalty problem: wrong features at long lead times are penalized more than wrong features at short lead times.

- Squared Loss: Encourages spectrum to match the data.

- MSE for bias: Batch average mean amplitude of the bias.

Trained on three days rollout data. Remained stable for year-long simulations.

Stochastic GCM

Introduces randomness to be able to produce ensambles of forecasts.

Loss is CRPS (Continuous Ranked Probability Score) = Mean absolute error + Variance in ensamble spread

Structured State Spaces

Introduction

Especially suitable for long and continuous time series (speech, EEG, ...).

Use seq to seq map to map input to a latent space.

<B, L, D> --> <B, L, D>

Much more efficient than Transformers, both computationally and memory wise. Also better at modelling long term dependencies.

Model

These are continuous time models (CTMs), which also allow for irregular sampling.

State Space Models (SSM) are parameterized by matrices A, B, C, D, and map an input signal \( u(t) \) to output \( y(t) \) through a latent state \( x(t) \). Recent theory on continuous-time memorization derives special A matrices that allow SSMs to capture LRDs mathematically and empirically. (Right) SSMs can be computed either as a recurrence or convolution.

Drawbacks are that are inefficient and prone to vanishing gradients. S4 introduces a novel parameterization that efficiently swaps between these representations, allowing it to handle a wide range of tasks, be efficient at both training and inference, and excel at long sequences.

Combine strength of the former models into State space models (SSMs):

- Seq to seq: discretization of continuous sequence

- RNN: hidden memory state

- CNN: efficient computation and parallelization ability

\( u(t) \leftarrow y(y) \)

where \( u(t) \) is the input and \( y(t) \) is the output.

\( x'(t) = Ax(t) + Bu(t) \) \( y(t) = Cx(t) + Du(t) \)

where \( x(t) \) is the hidden state space, \( u(t) \) is the input, \( y(t) \) is the output we are trying to predict, \( A \) is the most important matrix called state matrix. \( x(t) \) can be a continuous function or a discrete sequence obtained by sampling.

How do we initialize the state matrix so that it handles long term dependencies?

(these matrices are not learned)

The Hippo approach allows memorization of the input (input reconstruction), even after a long time. It works by encoding the data with Legendre polynomials, which are orthogonal and can be computed efficiently. It allows to fully describe the input sequence even after long sequences.

The idea is to condition A with low rank correction (computable as Cauchy kernel). A can be computed with the Hippo method, continuous time memorization (set of useful matrices).

-

To discretize: sample from the continuous function \( x(t) \) at discrete time points \( t_i \) Convert A to discrete time matrix \( \hat{A} \) using the formula: \( \hat{A} = (I - \frac{\delta}{2}A)^{-1} (I + \frac{\delta}{2}A) \)

-

To convolution: simply unroll the timesteps into a single dimension and apply a convolutional layer, this allows parallelization

With discrete representation, the efficiency is on par with RNNs. This is the reason the frequency domain is used to apply convolutions, which allows for efficient parallelization.

Results

A general purpose model, which can be applied to continuous, recurrent and convolutional tasks and spaces. It is also efficient, both in terms of memory and computation, and performs better than other models (even transformers) on long sequences.

MaxViT

Makes use of a new scalable attention model (multi-axis attention).

- Blocked local attention: attention is only computed within a block of tokens.

- Dilated global attention: attend to some tokens is a sparse way.

Allows for linera complexity interactions between local/global tokens.

Normally attention requires quadratic complexity, but this is reduced to linear complexity. Attention is decomposed into local and global attention (by decomposing spatial axis).

Given:

\( x \in R^{H \times W \times C} \)

- Normal attention flattens the H and W dimensions into a single one.

- Block attention separates the token space into \( < \frac{H}{P} \times \frac{W}{P}, P \times P, C > \) non overlapping windows, each of \( P \times P \) size.

- Grid attention subdivides the token space into \( < G \times G, \frac{H}{G} \times \frac{W}{G}, C > \), where each grid point is uniformly spread over the token space.

Using both block and grid attention, we can compute attention in linear time and have interaction between local and global tokens. Normally block attention underperforms on large token spaces, as it is not able to capture long range dependencies.

Hiera ViT

Introduction

Hiera ViT is a hierarchical vision transformer that removes additional bulk operations deemed unnecessary. Several components can be removed without affecting performance. This leads to a more simple and accurate model, which is also faster.

Hiera

Uses strong pretext task (with Masked autoencoder) to teach spatial bias. Local attention is used inside the mask units.

The problem when using masked autoencoders is the fact that we hide coarser information and we proceed deeper in the network. To avoid this, sparse masking is used (deletes patches, not overrides them). This also keeps the difference between token (internal feature representation of the model) and masked units (fixed size across layers).

The baseline used is MViTv2, which learns a multiscale representation of the image over 4 stages. First it learns low level features (but high spatial resolution), then at each stage trades channel capacity for spatial resolution.

Pooling attention is used mostly to reduce the dimensionality of the input (especially for K and V, while Q is pooled to transition between stages by reducin spatial resolution).

Simplifications

Relative Positional Embedding

This module was added to each attention block to allow the model to learn relative positional information. This is not necessary when training with MAEs, and absolute positional embeddings can be used.

Remove Convolutions

Convolutions add unnecessary overhead since they provide benefits only when dealing with images. These are replaced with maxpools, reducing the accuracy of the model by 1.0%, however, when removing also maxpools with stride==1, the accuracy is nearly the same as the original one, but 22% faster.

Remove Overlap

Maxpools with 3x3 kernel size cause an issue of dimensionality, which is normally fixed with "separate and pad" technique. By avoiding overlaps between maxpools, this stage is unnecessary as kernel size equals to stride. The accuracy stays the same, but the model is 20% faster.

Remove Attention Residual

Attention residual is used as it helps to learn the pooling attention. It is used between Q and the layer output.

Mask Unit Attention

Mask unit attention is used to learn the spatial bias as well as for dimensionality reduction (removing it would slow down the model). Instead local attention is used within the unit masks, so that tokens are grouped already once they arrive at the attention block. We can then perform attention within these groups (units).

Results

The model is 100% faster than the baseline, while remaining at the same accuracy for images.

For videos, the model is 150% faster, and accuracy is increased by 2.5%.

Swin Transformer

Introduction

Hierarchical Vision Transformer, representation is computed with shifting window. Self attention is limited non overlapping local windows. Allows for cross-window attention.

Architecture

Patch size is 4x4 and 3 rgb channels. Linear embedding is applied to the patch, and size is constant C. Swin attention is then applied and patch merging is done for 2x2 neighboring patches. Token reduction by 4:

\( \frac{H}{4} \times \frac{W}{4} \rightarrow \frac{H}{8} \times \frac{W}{8} \)

Output dimension is set to 2C.

Swin Attention

The swin transformer block replaces standard self attention with a sliding window attention, linear MLP layerm and GeLU activation function. Before attention layer normalization is applied.

The swin self attention is computed within a local window of size \( M \times M \), which makes it more scalable then normal self attention.

This approach lacks connection cross window, so cross window attention is introduced. This method uses shifted windows partitioning, which alternates between two partitioning configurations.

- Partition 8x8 feature map into 2x2 windows;

- Shift next layer from the previous by displacing the window.

How to compute attention efficiently?

Several windows in the same batch can be created with with cycling shifting process.

Relative Bias Problem

Add bias matrix B before softmax computation.

\( Attn(Q, K, V) = softmax(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}} + B) V \)

where B is a learnable matrix of size \( M^2 \times M^2 \), and \( M^2 \) is the number of patches in a window. This matrix can also be optimized by approximation, making it smaller with smaller window size:

\( B \in R^{M^2 \times M^2} \rightarrow B ~ \hat{B} \in R^{(2M-1) \times (2M-1)} \)

Variations of Swin Transformer model

| Model | C | Layer sizes | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swin-B | 96 | <2, 2, 6, 2> | 29M |

| Swin-T | 96 | <2, 2, 18, 2> | 50M |

| Swin-S | 128 | <2, 2, 18, 2> | 88M |

| Swin-L | 192 | <2, 2, 18, 2> | 88M |

Swin Transformer V2

Introduction

Swin Transformer V2 is an improved version of the Swin Transformer, which is a hierarchical vision transformer. It is designed to scale up to higher capacity and resolution.

Some problems with the original Swin Transformer are:

- tranining instability

- resolution gaps

- hunger for labeled data

Architecture and solutions

For the previous problems, the following solutions are proposed:

Residual post norm method

The residual post norm method is used to stabilize training. It replaces the pre-norm residual connection used in Swin Transformer with a post-norm residual connection.

The output of the residual block is normalized before merging with the main branch (amplitude of the main branch does not accumulate in the residual branch). This means the activation amplitudes are much milder, which makes training more stable.

Cosine Attention

Scaled cosine attention is used instead of dot product attention.

\( Sim(q_i, k_j) = \frac{cos(q_i, k_j)}{\tau} + B_{ij} \)

where \( B_{ij} \) is the relative position bias matrix between pixels i and j, while \( \tau \) is a learnable scaling factor.

Log-Spaced continuous bias term

The coordinates are log-spaced, which allows for better resolution of the attention map.

\( \hat{\Delta x} = sign(x) log(1 + \Delta x) \)

where \( \hat{\Delta} x \) is the new log spaced coordinate, and \( \Delta x \) is the original coordinate.

The bias term also uses log-spaced continuous relative positions, instead of the parametrized approach.

Self-supervised pre-training (SimMM)

This method avoids the need for many labeled samples.

Scaling up model capacity

The Swin Transformer V2 is scaled up by increasing the number of layers and channels. There are two main issues with this approach:

- Instability when increasing the number of layers: activations at deeper layers increase drammatically, creating a problem of discrepancy between layers of the network;

- Degrade of performance when transfering to different resolutions.

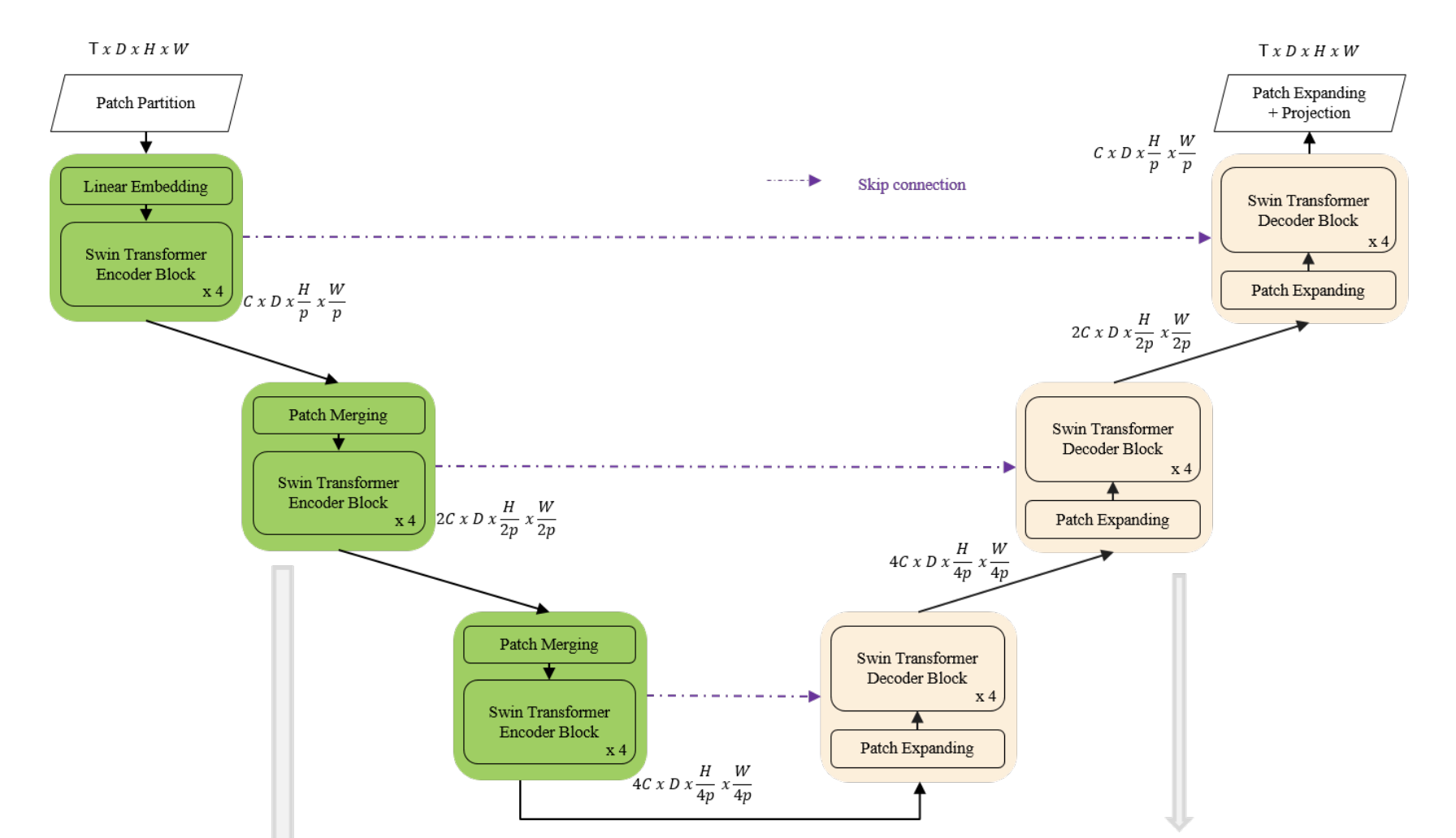

Spatio-Temporal Swin-Transformer

Input to the model is 4D with the addition of the temporal dimension.

The input video is defined to be of size T×H×W×3, tokenization is 2x4x4x3: In Video Swin Transformer, we treat each 3D patch of size 2×4×4×3 as a token, while the channel size is not patchified.

Spatial downsampling is applied to reduce the embedding space. We used a fully connected layer to scale up the dimension of the incoming data.

The proposed network is tested on the Weather4Cast2021 weather forecasting challenge data, which requires the prediction of 8 hours ahead future frames (4 per hour) from an hour weather product sequence.

This paper used 3D patch embedding, 3D shifted window multi-head self attention as well as patch merging. This paper has 2d variables as channel dimension is not patchified. In my case we'll need to create 4D patch embedding as also height layer has to be partitioned.

Multi-scaled stacked ViT

Development of an efficient ViT:

- Adds a layer normalization after the patch embedding operation;

- Global and Local token differentiation;

- Self-attention mechanism is replaced with efficient multi-scaled self-attention mechanism;

- Positional embedding 1-D is replaced with 2-D positional embedding or absolute positional bias.

Multi-scaled self-attention mechanism

Uses a local attention plus global memory approach. Define the n_g global tokens that are allowed to attend to to all tokens, and the n_l local tokens that are allowed to attend to the tokens in their local 2D window area and only the global tokens.

Relative positional bias: add a bias matrix to each head when capturing the attention score (makes the transfomer translation invariant).

Theoretical complexity: n_g and n_l are global and local token numbers, the memory complexity is \( O( n_g(n_g + n_l) + n_l w^2 ) \).

Comparisons

Linformer: projects \( n_l \times d \) dimensional keys and values to \( K \times d \) with an additional linear projection layer, where \( K << n_l \). The memory complexity in this case is \( O( K n_l ) \) where K is a constant, usually set to 256.

Performer: uses random kernels to approximate the softmax in MSA.

How to compare? It depends a lot on the trade-offs. More aggressive spatial resolution makes accuracy worst, but performance is much better (or memory cost manageable).

Why is longformer better? Conv-like sparsity gives better inductive bias for ViTs. Or, the Longformer keeps keys and values at high resolution.

Linear Transformers

Introduction

How to rout information in a sequence of tokens? -> We use query + key matrices

- Query: what we are looking for (what info we want to extract)

- Key: what type of info the node contains (what info we have)

Inner product is used to rout (similarity between query and key). This is called soft-routing as it is a weighted average of all the keys (where inner product is larger).

Complexity is \( O(n^2) \), where n is the number of tokens (sequence length), embedding size is d.

\( Q \times K = n \times n \) -> where multi-head attention doesn't help, but the n matrix could be simplified into n/heads matrix.

Ex. 4 heads -> 512 / 4 = 128

We can approximate Q into a low rank matrix, and complexity would be reduced to \( O(n) \).

Linear Transformer

\( \text{Attention} = \text{softmax}(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}})V \)

If the term inside the softmax is low rank, then we can reduce computation.

Eigenvalues of Q and K can be used to determine if matrix needs to be high or low rank. Results show that most of the times 128 is enough.

How to reduce dimensionality? We can use a random projection P before the self-attention layer.

\( \text{Attention} = \text{softmax}(\frac{Q(EK)^T}{\sqrt{d_k}})FV \)

So we introduce the E and F matrices (fixed, not learned). The term inside the softmax becomes nxk, while FV is kxn. The shapes so are correct for matmult.

Results

With large sequence lengths, the linear transformer keeps inference times constant, as it doesn't depend on the sequence length n but also on k. Complexity is reduced from \( O(n^2) \) to \( O(nk) \).

How to choose k?

\( k = \frac{5\log(n)}{c} \)

So it depends on n still? Complexity is \( O(n\log(n)) \) now.

However we can make it linear:

\( k = min { \theta(9d \log(d)), 5\theta(\log(n)) } \)

In the first case it is linear in d, in the second case it is linear in n. We can choose the minimum of the two. So it's enough to downproject the matrix to a dimension of about d.

Linear Transformers as FWP

Introduction

The concept of fast weight programmers (FWP) is introduced in this paper.

The idea is to use a slow network to program by gradient descent the weights of a fast network. FWP learn to pmanipulate the content of a finite memory and dynamically interact with it.

Linear transformers have constant memory size and time complexity linear which depends on the sequence length. The time complexity is reduced thanks to the linearization of the self-attention layer and softmax operation.

Linear Transformers as FWP

In normal neural networks, the weights are fixed and the input is manipulated, while the activation is input dependant and can change at inference time. The idea of FWP is also have the weights variable and input dependent (synaptic modulation).

- Context-dependent -> slow weights

- Context-independent -> fast weights

The process revolves around a slow network which is trained to program the weights of the fast network. This makes the fast weights dependent on the spatio-temporal context of the input stream.

Which instructions to use? Outer product:

\( a^{(i)}, b^{(i)} = W_ax^{(i)}, W_bx^{(i)} \) \( W^{(i)} = \sigma (W^{(i-1) + a^{(i)} \oplus b^{(i)}}) \) \( y^{(i)} = W^{(i)} x^{(i)} \)

The outer product is \( \oplus \), \sigma is the activation function, W_a and W_b are the trainable slow weights, while W is the fast weight matrix.

Linearizing self-attention

Instead of removing the softmax, prior works have introduced techniques for linearizing the softmax. This improves the computational efficiency of the self-attention layer for long sequences.

An important term is the softmax kernel \( \kappa(k, q) = exp(k \dot q) \), which in linear self-attention is approximated by another kernel \( \kappa'(k, q) = \phi(k)^T \phi(q) \).

Since the embedding space for keys is limited, there is only room for d orthogonal vectors. If the length of the sequence is larger than d, th model might be in a overcapacity regime. In this case the model should dynamically interact with the memory content and determine which association to remember and which one to forget. On the other hand, the standard transformer stores associations as immutable pairs, increasing its memory requirements.

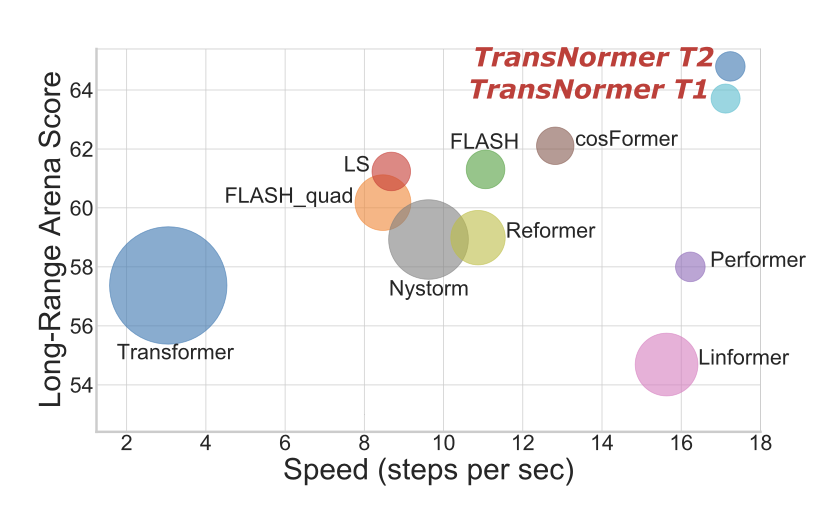

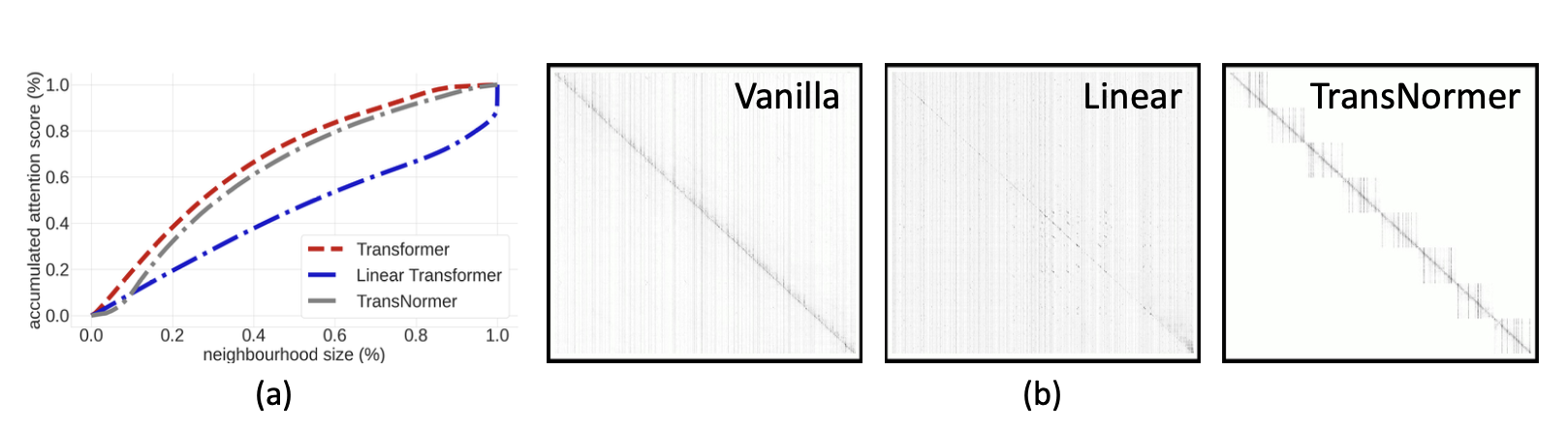

The Devil in Linear Transformers

Summary

Kernel based linear transformer have two main problems:

- Unbounded gradients: which negatively affect convergence (the problem comes from the scaling of the attention matrix);

- Attention dilution: which trivially distributes attention scores along large sequences.

The authors propose a solution to both problems by introducing a new model, the Transnormer. The idea is to used vanilla attention, which is more accurate and causes less dilution, in conjunction with linear attention, which is more efficient and scalable.

- Diagonal attentin is used for the early stages of the network, to address dilution;

- Norm attention is used in later stages, to stabilize training gradients.

Can we just remove scaling from linear attention? No, because it would cause a drop in accuracy (ppl). The cause is that the attention map becomes unbounded in the forward pass. We want to bound attention map in forward, as well as gradients in backward pass.

Attention without scaling can be calculated as follows:

\( O = Q(K^TV) \) \( O_{norm} = X_{norm}(Q(K^TV)) \)

where \( X_{norm} \) is a normalization layer.

Diagonal attention on the other hand is created by leveraging a non-overlapping blocks strategy for the attention distribution. This reduces time complexity as attention is calculated inside each block.

Complexity is given by:

\( O(nwd) \)

where \( n \) is the sequence length, \( w \) is the block size, and \( d \) is the feature dimension.

This concludes that these models require global attention in later stages, while local attention is sufficient in early stages.

Do Vision transformers share the same issues?

Performer

Estimates regular self attention with provable accuracy in linear space and time complexity. Uses Fast Attention Via Orthogonal Random Features (FAVOR+) to approximate the softmax attention mechanism. (Scalable kernel method)

Normally attention is calculated as follows:

\( Attn(Q, K, V) = D^{-1}AV \)

Where \( A = exp(QK^T / \sqrt{d}) \) and \( D = diag(A1_L) \) (1 is a vector of ones)

The Performer approximates the softmax attention mechanism by using orthogonal random features. The attention mechanism is approximated as follows:

\( Attn(Q, K, V) = \hat{D}^{-1}\hat{A}V \)

Where \( \hat{A} = tril(A) \) and \( \hat{D} = diag(\hat{A}1_L) \), and tril() returns the lower triangular part of the argument matrix including the diagonal.

The attention matrix can be calculated in \( O(Ld^2 log(d)) \) where \( L \) is the sequence length and \( d \) is the hidden dimension. While normally the attention matrix is calculated in \( O(Ld^2 log(L) ) \) time.

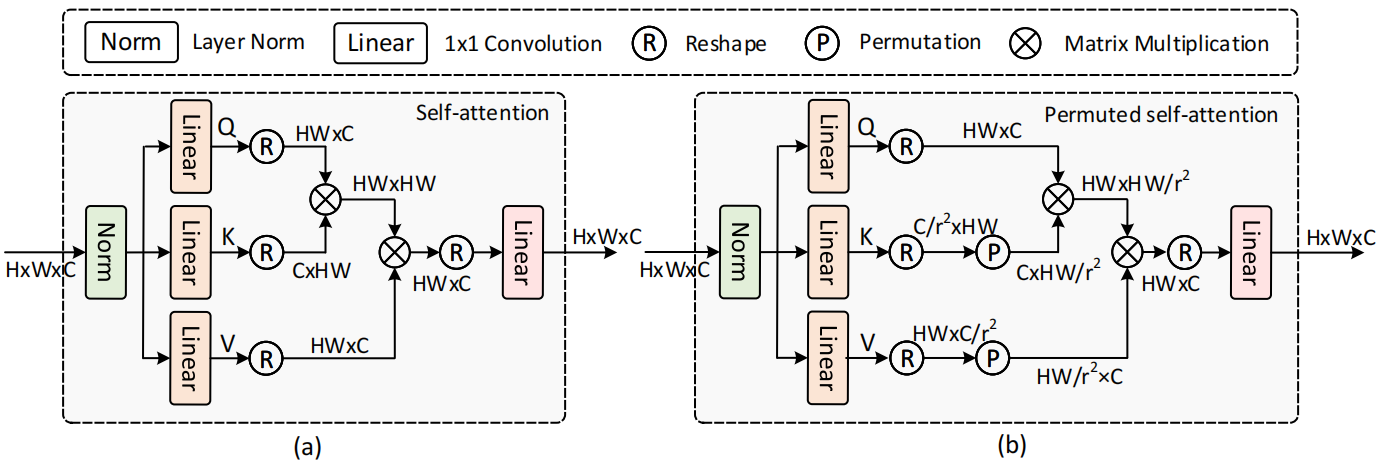

SRFormer

Introduces permuted self attention, which can be added to the normal window self-attention.

How do we increase the attention window without increasing the complexity?

Given a feature map X and a token reduction factor r, we first split X into non overlapping square windows with side length S. The result is then passed through 3 linear layers to get Q, K and V.

Compress K and V size to \( \frac{NS^2}{r^2C} \), then permute the spatial tokens in K and V to the channel dimension, obtaining K_p and V_p.

The self-attention window size becomes \( \frac{S}{r} \times \frac{S}{r} \), but C is unchanged.

The performance gain is obtained when downscaling the spatial dimension, as the complexity of the attention mechanism is reduced.

Test time training (TTT)

- Transformers: O(N^2) complexity due to self-attention.

- Mamba and advanced RNNs: O(N) complexity, but latent space is fixed, still subject to catastrophic forgetting

TTT methods

New class of sequence modelling layers where the hidden state is a model, and the update rule is a step of self-supervised learning. The process is updating the hidden state even during the test time.

Self attention has hidden state growing linearly with the sequence length (cost is per token), while TTT has a fixed size hidden state.

TTT compresses the historical context into a hiddden state St, making the context an unlabelled dataset.

Test Time Training ++

Can TTT always mitigate distributional shift? This paper shows an improved version of TTT

TTT adapts neural networks to new data distributions at test time on unlabeled samples, using two tasks:

- Main task (classification)

- Auxiliary task (SSL reinforcement)

When does it fail?

- When the auxiliary task is not informative

- When the auxiliary task overfits --> main task may worsen

Solution: Online feature alignment (domain adaptation with divergence measure). After training we have offline feature summarization (mean and std calculation), channel wise batch norm using stats just calculated, then test time regularization minimizing the distance between test and train samples.

- Online dynamic queue

TTT-A: alignment of features (first + second order statistics) TTT-C: contrastive learning addition (SSL on target domain)

TTT++: TTT-A + TTT-C

Limits: feature summarization + resnet backbone

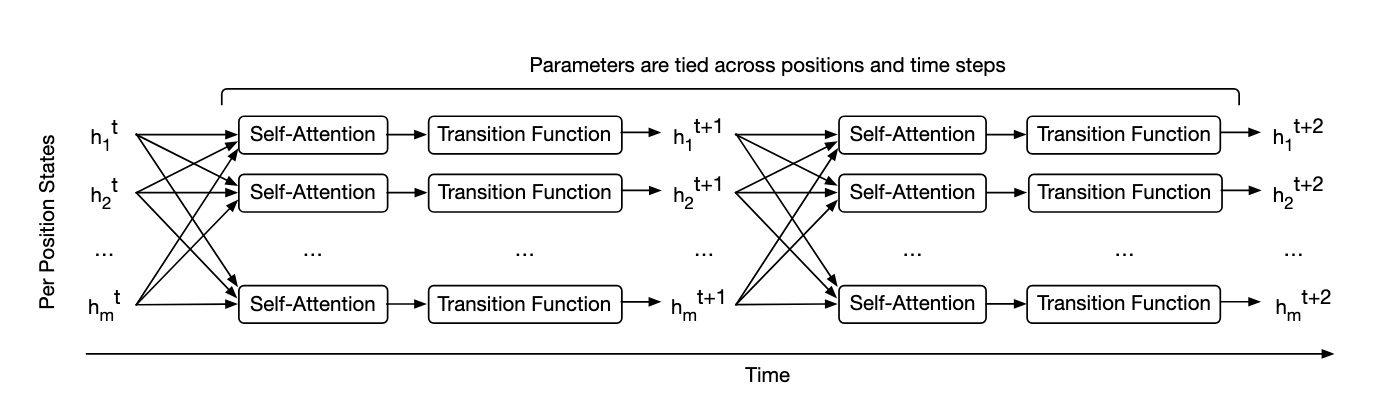

Universal Transformers

RNNs: slow in training

Feedforward and conv architectures have achived better performance in many tasks, but transformers fail in generalizing for simple tasks.

Universal Transformers: parallel in time, self-attentive RNN, combines recurrent nature + simple parallelization of transformers. It can also be tuting complete if given enough data (SOTA performance on many tasks).

UT refines a series of vector representations at each position of the sequence in parallel. It combines info with self-attention + recursive transition function across all time steps.

How is efficiency?

With enough computation, UT is computationally universal.

The Rise of Data-Driven Weather Forecasting

Summary

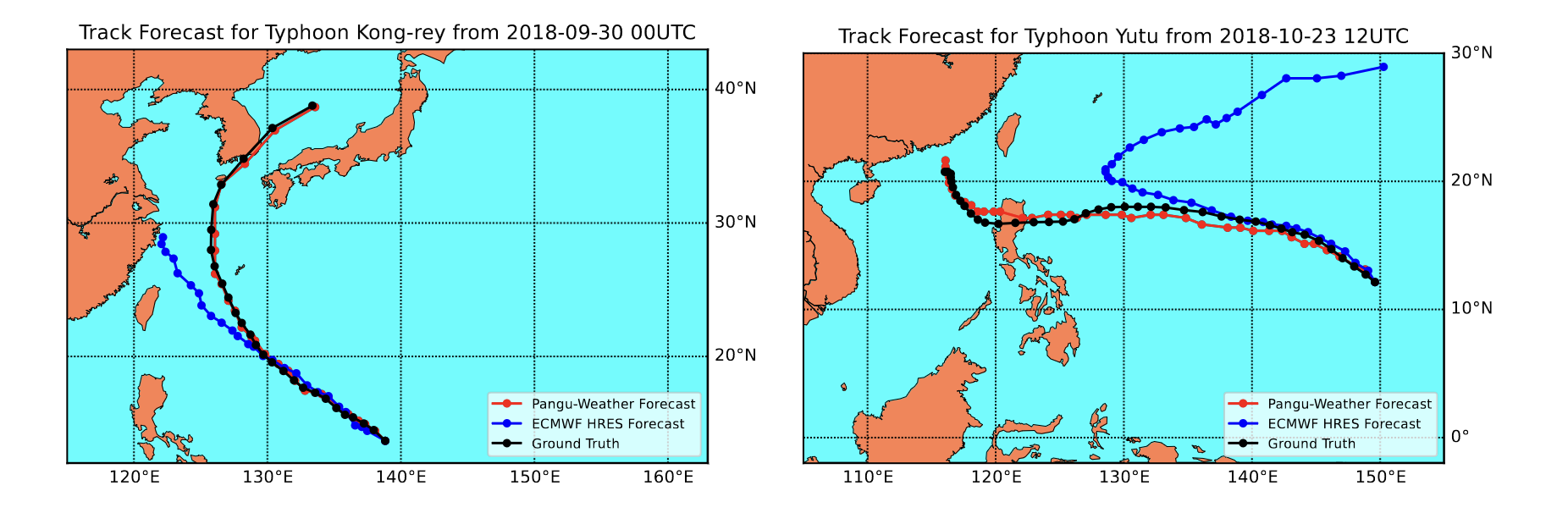

Comparison between AI based forecasts and NWP forecasts in operational-like context. The rise was due to the availability of large datasets and the development of new models. Examples include ERA5 reanalysis (28km resolution, 0.25 degs, 1979-2019). The use of this dataset however renders the resolution of the models to be lower compared to IFS, which is 9km.

Comparison Pangu-IFS:

- Statistical consistency of the model: IFS is better than PGW, which is far from perfect reliability. Can the model predicti extreme events with the same probability as the observations? (or is it just blurring?) Used example is the one of tropical cyclones.

- Forecast error prediction: general agreement between PGW and IFS in daily mean error.

ClimaX

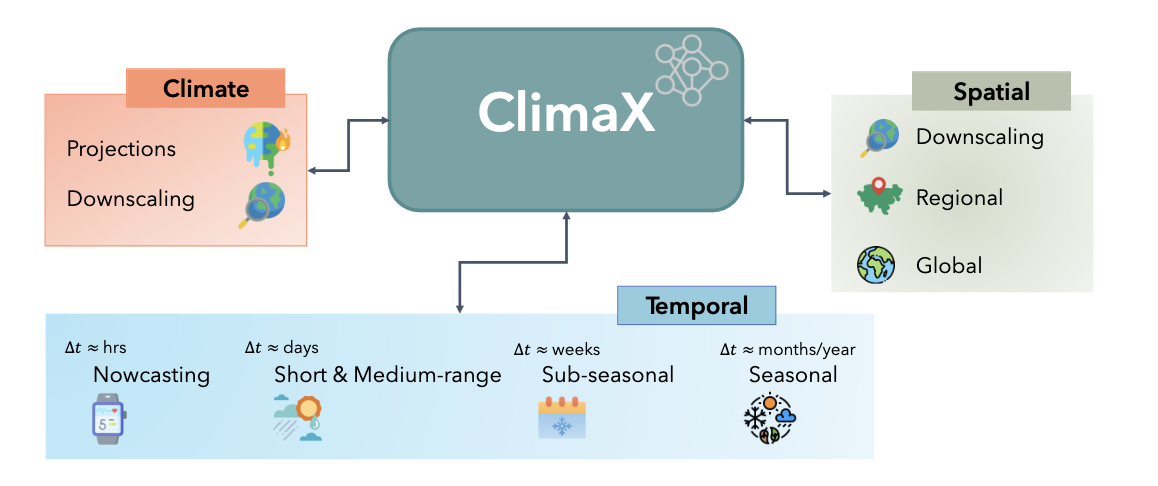

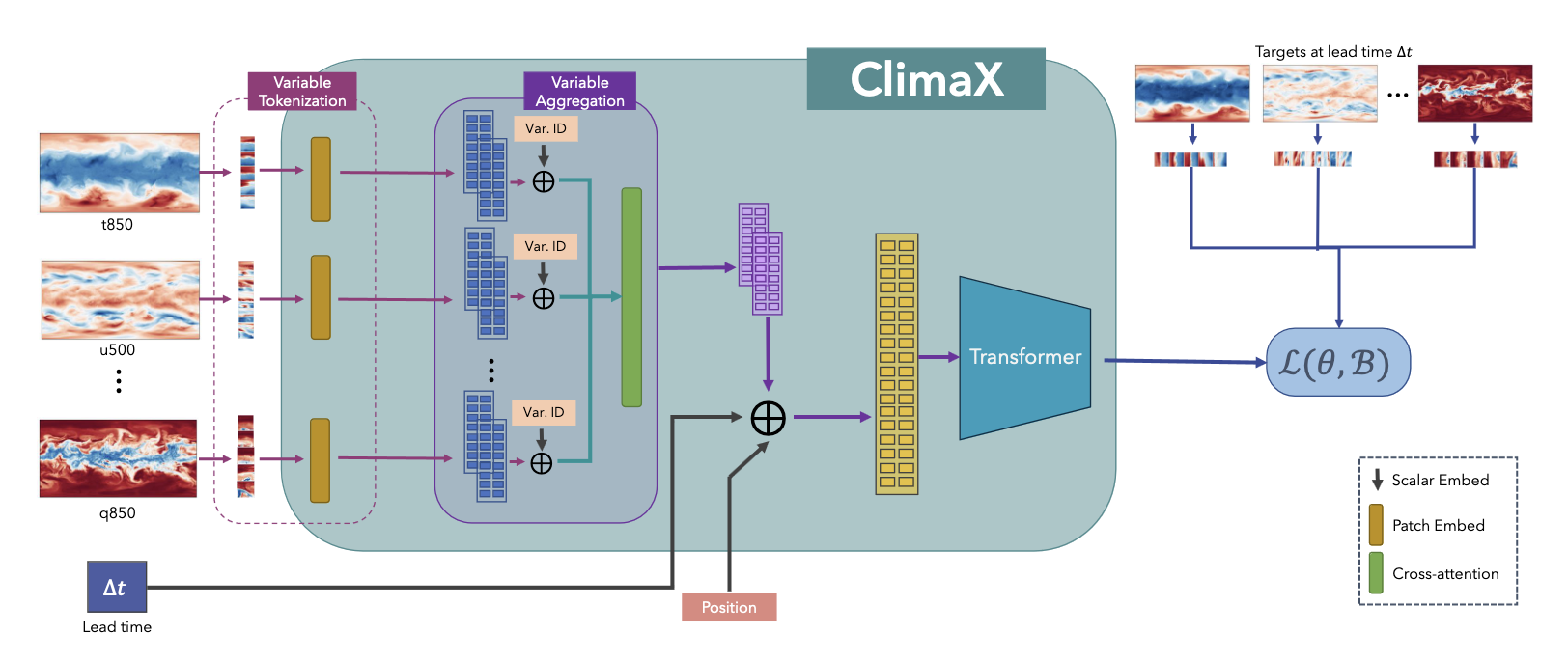

ClimaX is a foundation model designed to be pre-trained on heterogeneous data sources and then fine-tuned to solve various downstream weather and climate problems.

The set of climate and weather variables is extremely broad, and predictions may be required for regional or even spatially incomplete data, even at different resolutions. Current CNN-based architectures are not applicable in these scenarios, as they require the input to be perfectly gridded, contain a fixed set of variables, and have a fixed spatial resolution. resolution. Transformer-based architectures, on the other hand, offer much greater flexibility by treating the image-like data as a set of tokens. As a consequence, the backbone architecture chosen is a Vision Transformer to provide greater flexibility.

Two significant changes to this model were implemented. The first change involved variable tokenization, which includes separating each variable into its own channel and tokenizing the input into a sequence of patches. The second change was variable aggregation, introduced to speed up computation by reducing the dimensionality of the input data and to aid in distinguishing between different variables, thereby enhancing attention-based training. After combining variables, the vision transformer block can produce output tokens that are then processed through a linear prediction head to recreate the original image. During the pre-training phase, a latitude-weighted reconstruction error is used to keep into account the location of the current patch. For fine-tuning, the ClimaX modules can be frozen, allowing for training only on the intended part of the architecture. In fact, often only the final prediction head and variable coding modules need retraining. This model has undergone testing for several downstream tasks, including global and regional forecasting and prediction for unseen climate tasks.

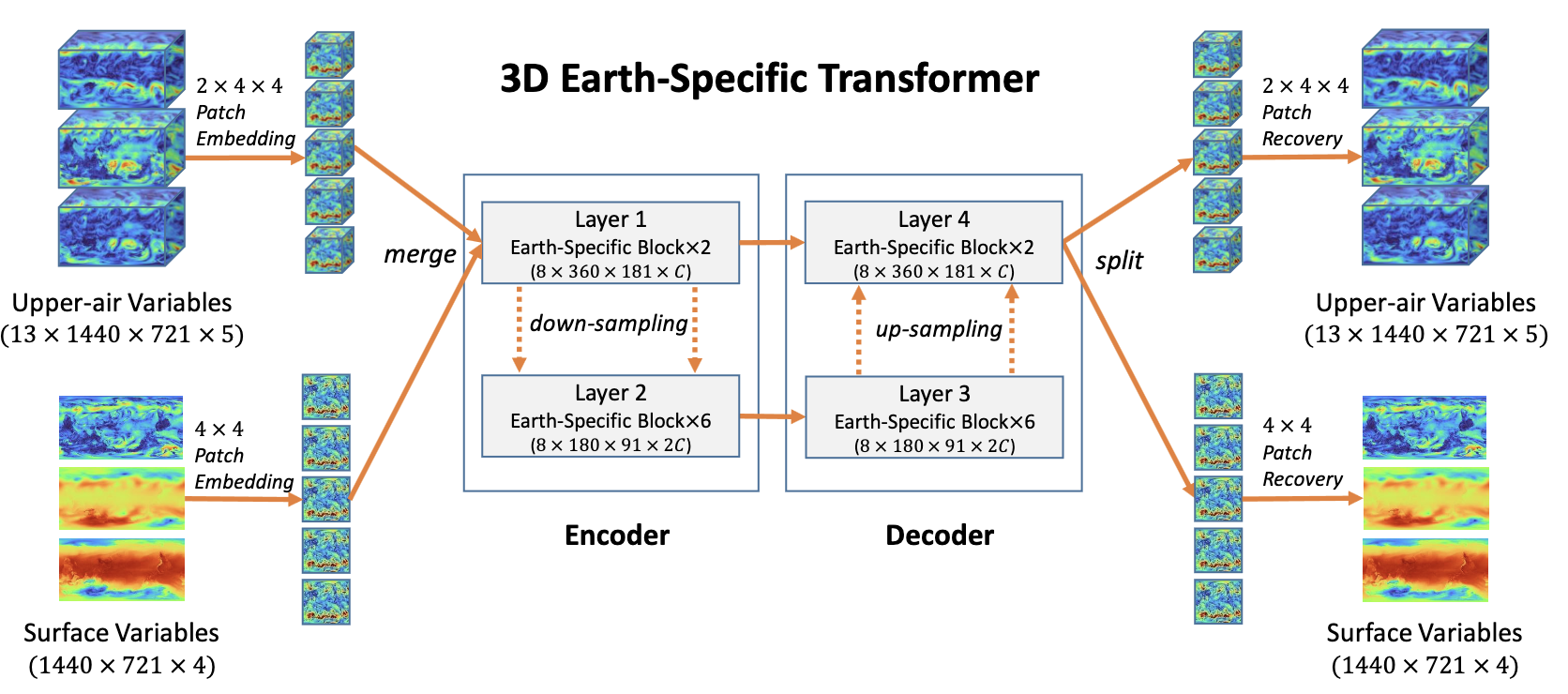

PanguWeather

Pangu Weather is a transformer architecture trained on three dimensional weather variables, as opposed to Climax, where all data was two dimensional. The lead time is also handled differently, with the model being trained to predict the weather at a certain time in the future, as opposed to the approach taken in the ClimaX work, where the lead time is passed as a parameter during the training phase.

The former approach is more similar to the one used in this project, where the simplicity of the dataset allows for a more straightforward implementation of the lead time, sacrificing some flexibility in the process. Finally, the Pangu weather model features some advanced techniques which separate it from all other competitors, namely the use of two different resolutions for the encoding of each variable, allowing the model to capture both large scale and small scale features, and use the attention mechanism to focus on different parts of the input data at the same time.

To achieve these two resolution, an encoder-decoder approach is used, where the encoder is tasked with the downscaling of input variables, and the decoder is tasked with the upscaling of the output. All transformer blocks are then applied to the output of the encoder, taking as input both the low and high resolution information.

MetNet 3

- Temporal resolution: 2 minutes

- Spatial resolution: 1 km

The network is a U-Net in conjunction with a MaxVit architecture

- Topographical embedding: automatically embeds time-indipendent variables (4km tokens) for 20 parameters

- U-Net: based on a fully convolutional neural network whose architecture was modified and extended to work with fewer training images and to yield more precise segmentation

- MaxVit: hybrid (CNN + ViT) image classification models.

Uses parameter oriented training for lead time (0 - 24 hours). Masks out with 25% probability a block of data.

FuXi

FuXi is an auto-regressive model for weather forecasting. The model is based on the U-transformer architecture, and is able to recurrently produce a prediction for the next timestep, given the previous predictions.

To generate a 15 days forecast, it is estimated it takes the model around 60 iterations, with a lead time of 6 hours. The loss utilized is multi-step, meaning it takes into account several timesteps at once, minimizing the error for each of them. This is in contrast with the approach taken in this project, where the loss is computed for each timestep individually. The U-transformer takes as input around 70 variables, for the current timestep, as well as the the preceding frame. All the variables used for this model are however restricted to two dimensions, ignoring any height layer. This architecture is a variation of the vanilla transformer model, and as opposed to the latter, before passing the encoded information to the self attention blocks, it downscales partially the input.

FourcastNet

FourcastNet is an architecture based on the Adaptive Fourier Neural Operator, which is a neural network model designed for high-resolution inputs, fused with a vision transformer backbone. The Fourier Neural Operator is a neural network architecture that uses a Fourier basis to represent the input data, allowing for the efficient computation of convolutions in the Fourier domain.

The use of this module allows to have a very small footprint in GPU memory, which is crucial for the training of large models. For instance, the base model used is around 10Gb in size, while analogue models with similar number of parameters have a size of around eight times as large.

GraphCast

Graphcast is a graph neural network architecture with an encoder-decoder configuration. The graph neural network is used to encode unstructured input data into a graph representation. As opposed to, for instance, convolutional layers where neighbouring information is encoded in a structured grid, graph layers use message passing between nodes to capture the relationships between different parts of the input data. This allows for the encoding of different kind of information, not necessarily restricted to a grid configuration.

One important hyperparamter to be set in this kind of architectures is the number of hops the messages containing neighbouring information are allowed to travel. This is crucial for the model to learn from the correct amount of knowledge, and allows for reducing the computational complexity of the model, as the number of hops is directly related to the time required for the model to train.

PrithViWxC (NASA FM)

2.3B Params, 160 variables from MERRA-2 (New ERA5)

Encoder-decoder architecture (MAE) ~50% masking operator probability

Tested on:

- Autoregressive rollout forecasting

- Gravity waveflux parameterization: small scale perturbations generated around thunderstorms

- Extreme event estimation

Max-ViT + HieraViT approaches:

- Axial Attention (with convolutional layers)

- Add convolutions at finetune to improve performance

- Local + Global attention Uses Flash Attention and FSDP

Validation with:

- Zero shot reconstruction

- Hurricane tracking

- Downscaling

MERRA2 dataset: cubed sphere grid, uniform grid spacing for each lat/lon (it minimizes grid spacing irregularities).

Climatology: instead of predicting delta from current time, we predict the delta from historical climate C_t. It is calculated from merra with 61 days of rolling average (it is computed across space and time).

Sigma^2_c = Sigma^2_c (x_t - C_t)

Normalization is also applied (10^-4 < sigma < 10^4, and 10^-7 < sigma_c < 10^7)

Scaling and training

Pretraining with 2 phases:

-

- 5% drop path rate, 50% masking operator probability, alternates global and local attention masking. Uses random forecast lead time (0, 6, 12, 24 hours). Train on 64 A100 GPUs, Batch size = 1, ~100000 gradient steps.

-

- 4 autoregressive steps with 80GB A100 GPUs. Use bfloat16 precision to shrink activation buffer sizes (and encoder / decoder size) while i/o remains f32

-

- 2 phases in pretraining with different masking ratios and params

Validation

- Masked reconstruction from zero-shot images

- Hurricane forecasting and tracking

Downstream applications:

- Downscaling for 2m precision + climatelearn benchmark

- Finetune for cordex downscaling

- Zero-shot masked reconstruction --> excels at short lead time prediction from minimal data.

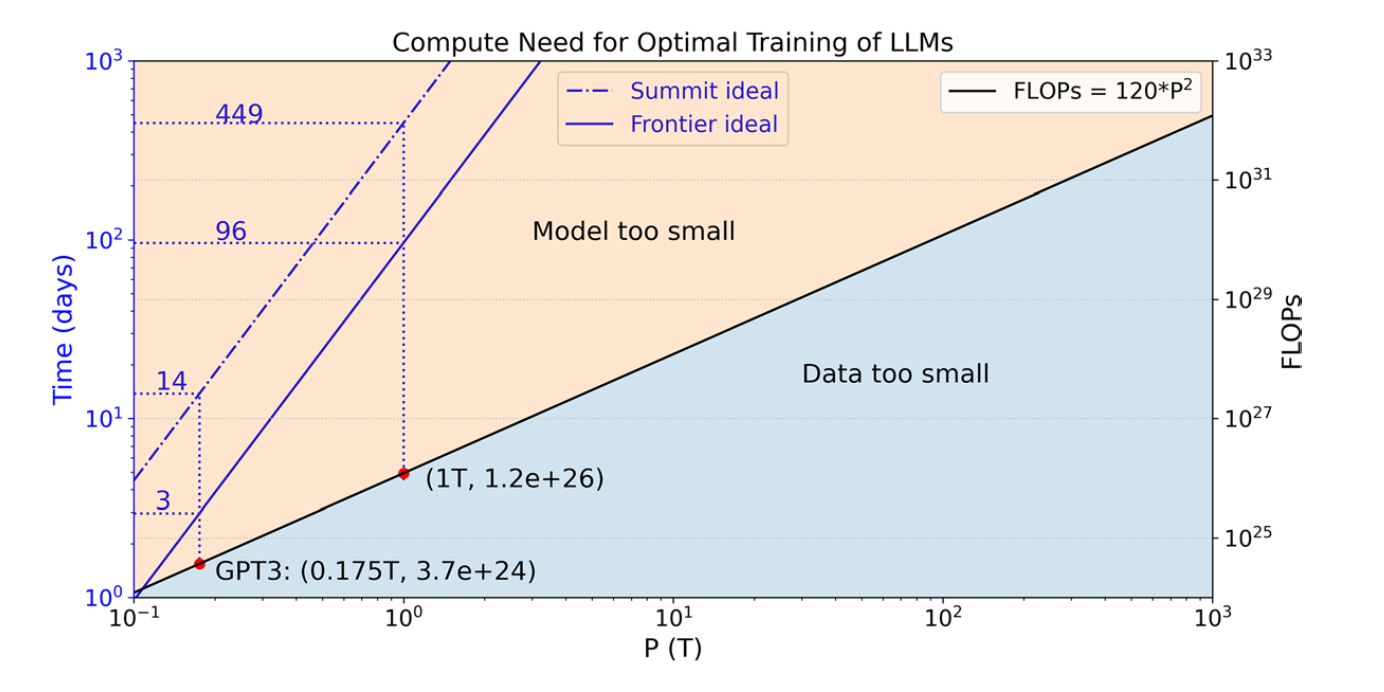

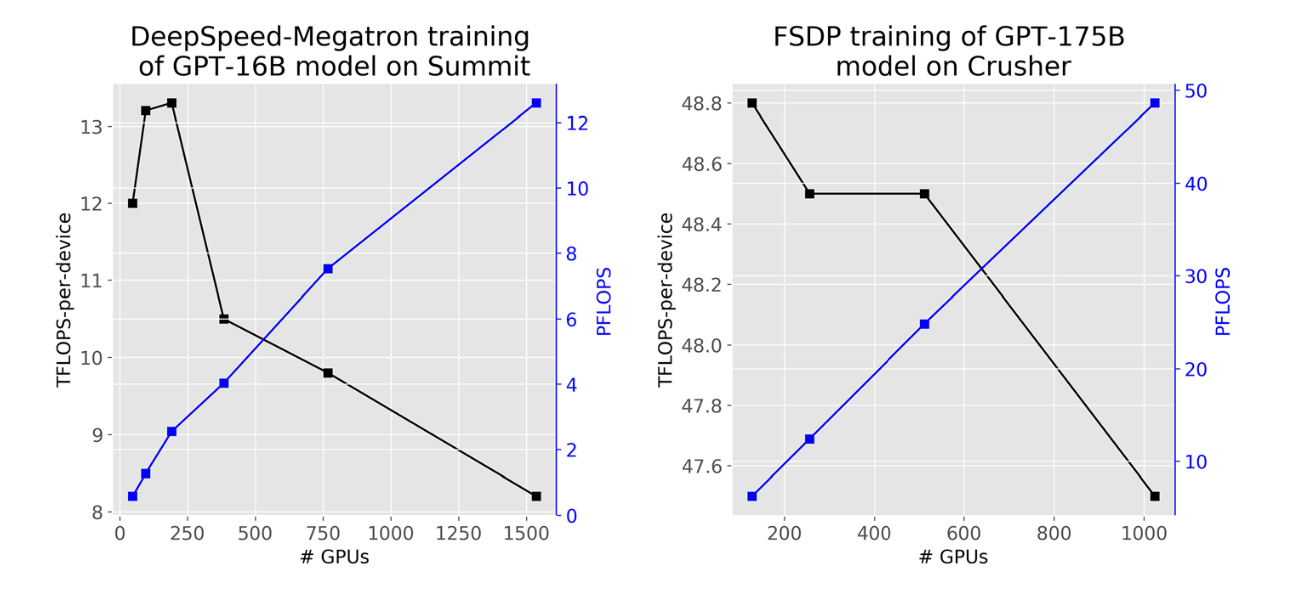

Oak Ridge base FM for Earth System Predictability

113B parameters with hybrid tensor data orthogonal parallelism technique (Hybrid STOP)

Uses unique math property of matrix chain multiplpication distributes model parameters in alternating row/columns shards. It combines tensor parallelism + FSDP. Better scalablity, avoids peak memory usage, keeps parameters shared through memory

y = xAB

It gathers partially and not globally, which makes the process faster on memory.

Uses 684 PetaFLOPS to 1.6 ExaFLOPS throughput across 49152 GPUs.

91 climate variables from 10 CMIP datasets, 1.2M data points.

Optimizations:

- Architecture optimization: problematic convergence with large attention logits (adds layer normalization before the self attention)

- Hierarchical parallelism: add also DDP on top of H-STOP (this speeds up training)

- Activation checkpoints: trade compute for memory savings in LLMs

- Mixed Precision: use bfloat16 to make large computations easier

- Layer wrapping: iterative FSDP sharding and prefetch

ClimateLearn

Summary

Aims at aiding climate forecasting, downscaling and projections.

It is a pytorch integrated dataset, composed mainly of CMIP6, ERA5 and PRISM data.

-

Forecasting: close to medium range weather and climate prediction

-

Downscaling: Due to large grid sizes, large cells are often used for reducing size of data. However, this leads to loss of information, and to a lower resolution predictions. Downscaling aims at correcting bias amd map results to higher resolution.

\( C \times W \times H \leftarrow C' \times W \times H \) where \( H < H' \) and \( W < W' \)

-

Projections: Obtaining long range predictions under different conditions (ex. greenhouse gasses emission or atmosphere composition).

The library also includes several baselines, pipelines for end-to-end training and evaluation, and a set of metrics.

ClimateBench

Summary

The aim is to simulate shared socio-economic pathways.

It is a benchmarking framework from CMIP, AerChemMIP, ScenarioMIP, and Detection-AttributionMIP. It also contains several ML models and full complexity Earth System Models (ESMs).

Mostly used for long term projections.

Also includes piControl (pre-industrial control, 500 years of points) and historical (historical forcing) simulations, which can be used for contrastive learning to reduce the amount of samples required by ML models, as for projections not enough data is available for deep learning training.

A possible challenge is applying ML and statistical learning to high-dimensional data. To this end Linear Transformers could be used.

WeatherBench

New benchmark to evaluate data-driven weather forecasting models (deep learning). The benchmark task is to predict pressure and temperature 3-5 days in advance.

The dataset used is ERA5 (40 years), regridded to lower resolution (bilinear interpolation) and usinfg 13 height levels:

- 5.625 degrees (32x64 grid)

- 2.8125 degrees (64x128 grid)

- 1.40625 degrees (128x256 grid)

Evaluation is executed on 2017 and 2018.

RMSE is used as the evaluation metric, also latitude-weighted RMSE.

Baselines:

- Operational NWP models (ECMWF, IFS)

- Linear Regression

- Simple CNN

Weather Challenges

- 3D atmosphere (CNNs might not work if used as channels)

- Limited train data (samples are correlated in time)

- Data is heavy to store in GPU memory

Extreme situations forecast: used as validation, to make sure the model is not just blurring (averaging) the predictions.

Key Features of WeatherBench

- Scientific Impact: of computing these models

- Challenge for data science

- Clear metrics for the climate domain

- Quickstart for users

- Reproducibility + communication between researchers

IPCC Working Group 1

The Current State of the Climate

It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land. Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere have occurred.

Global mean sea level increased by 0.20 [0.15 to 0.25] m between 1901 and 2018. The average rate of sea level rise was 1.3 [0.6 to 2.1] mm yr–1 between 1901 and 1971, increasing to 1.9 [0.8 to 2.9] mm yr–1 between 1971 and 2006, and further increasing to 3.7 [3.2 to 4.2] mm yr–1 between 2006 and 2018 (high confidence). Human influence was very likely the main driver of these increases since at least 1971.

Human-induced climate change is already affecting many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe.

Improved knowledge of climate processes, paleoclimate evidence and the response of the climate system to increasing radiative forcing gives a best estimate of equilibrium climate sensitivity of 3°C.

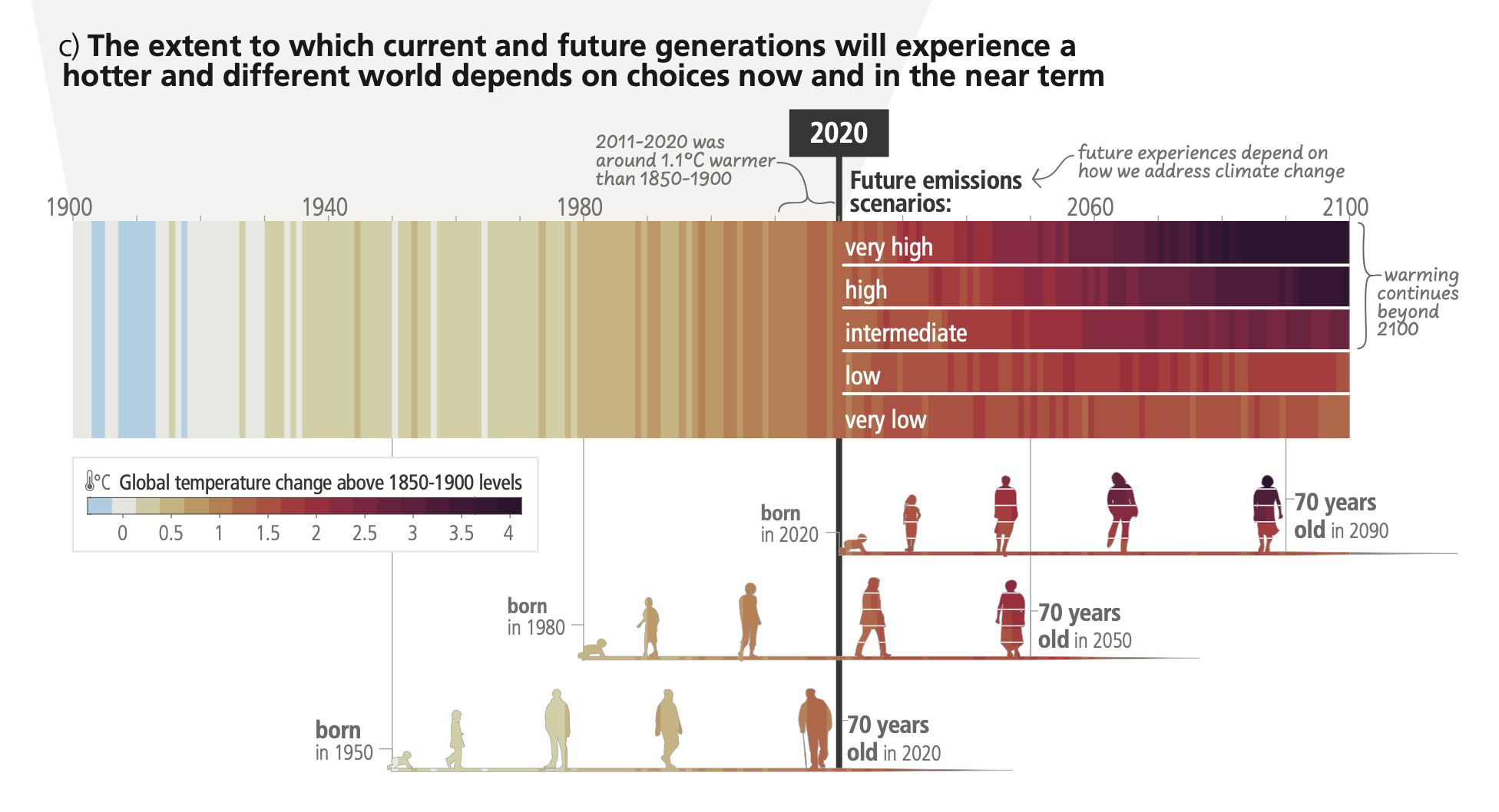

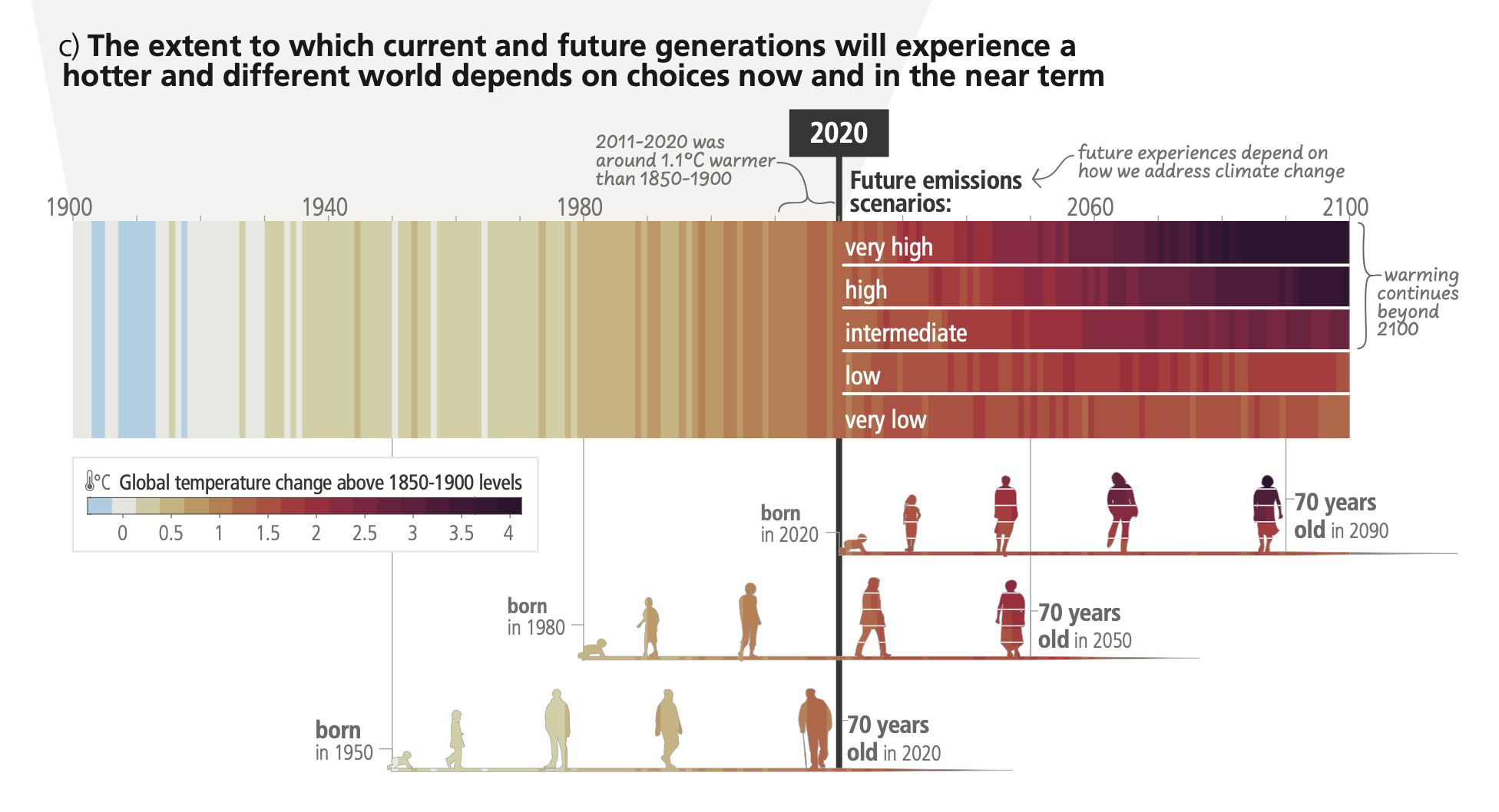

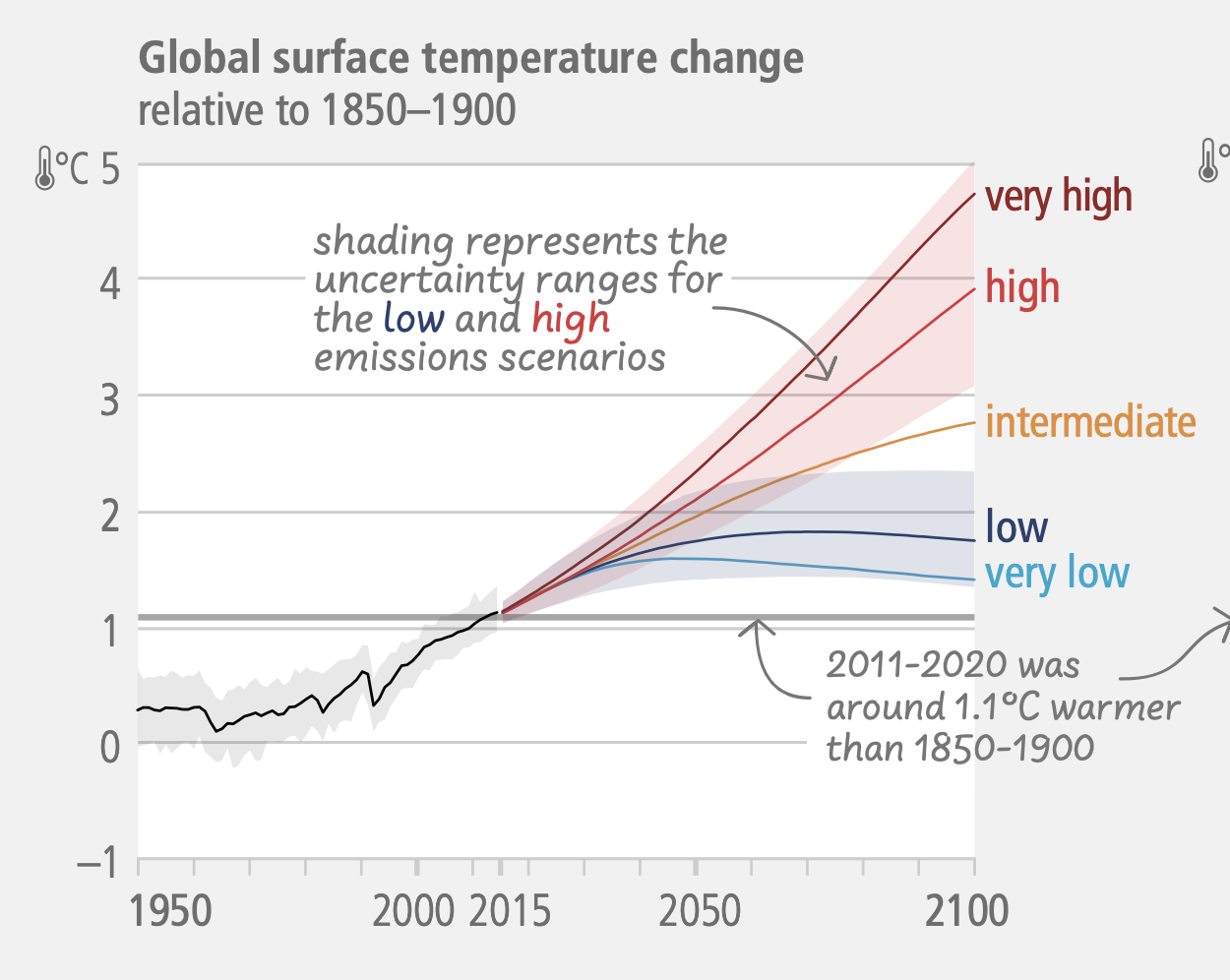

Possible Climate Futures

Global surface temperature will continue to increase until at least mid-century under all emissions scenarios considered. Global warming of 1.5°C and 2°C will be exceeded during the 21st century unless deep reductions in CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions occur in the coming decades.

Many changes in the climate system become larger in direct relation to increasing global warming. They include increases in the frequency and intensity of hot extremes, marine heatwaves, heavy precipitation, and, in some regions, agricultural and ecological droughts; an increase in the proportion of intense tropical cyclones; and reductions in Arctic sea ice, snow cover and permafrost.

It is virtually certain that the land surface will continue to warm more than the ocean surface. It is virtually certain that the Arctic will continue to warm more than global surface temperature, with high confidence above two times the rate of global warming.

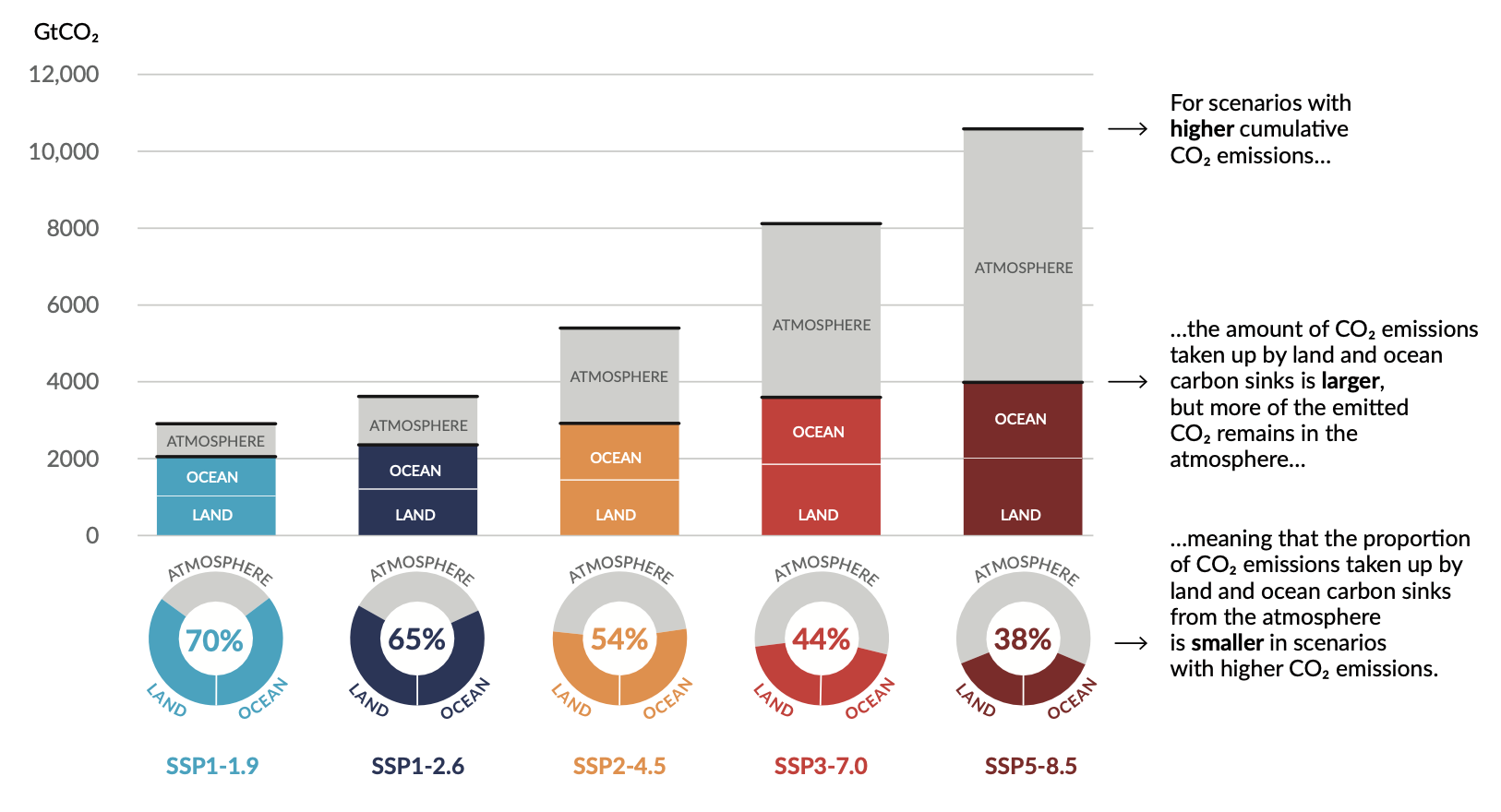

Continued global warming is projected to further intensify the global water cycle, including its variability, global monsoon precipitation and the severity of wet and dry events. Also, under scenarios with increasing CO2 emissions, the ocean and land carbon sinks are projected to be less effective at slowing the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere.

Many changes due to past and future greenhouse gas emissions are irreversible for centuries to millennia, especially changes in the ocean, ice sheets and global sea level.

IPCC Working Group 2

Observed and Projected Impacts and Risks

Human-induced climate change, including more frequent and intense extreme events, has caused widespread adverse impacts and related losses and damages to nature and people, beyond natural climate variability. Vulnerability of ecosystems and people to climate change differs substantially among and within regions driven by patterns of intersecting socioeconomic development, unsustainable ocean and land use, inequity, marginalization, historical and ongoing patterns of inequity such as colonialism, and governance.

Current unsustainable development patterns are increasing exposure of ecosystems and people to climate hazards.

Risks in the near term (2021–2040)

Global warming, reaching 1.5°C in the near-term, would cause unavoidable increases in multiple climate hazards and present multiple risks to ecosystems and humans.

Mid to Long-term Risks (2041–2100)

Beyond 2040 and depending on the level of global warming, climate change will lead to numerous risks to natural and human systems. The magnitude and rate of climate change and associated risks depend strongly on near-term mitigation and adaptation actions, and projected adverse impacts and related losses and damages escalate with every increment of global warming

IPCC Working Group 3

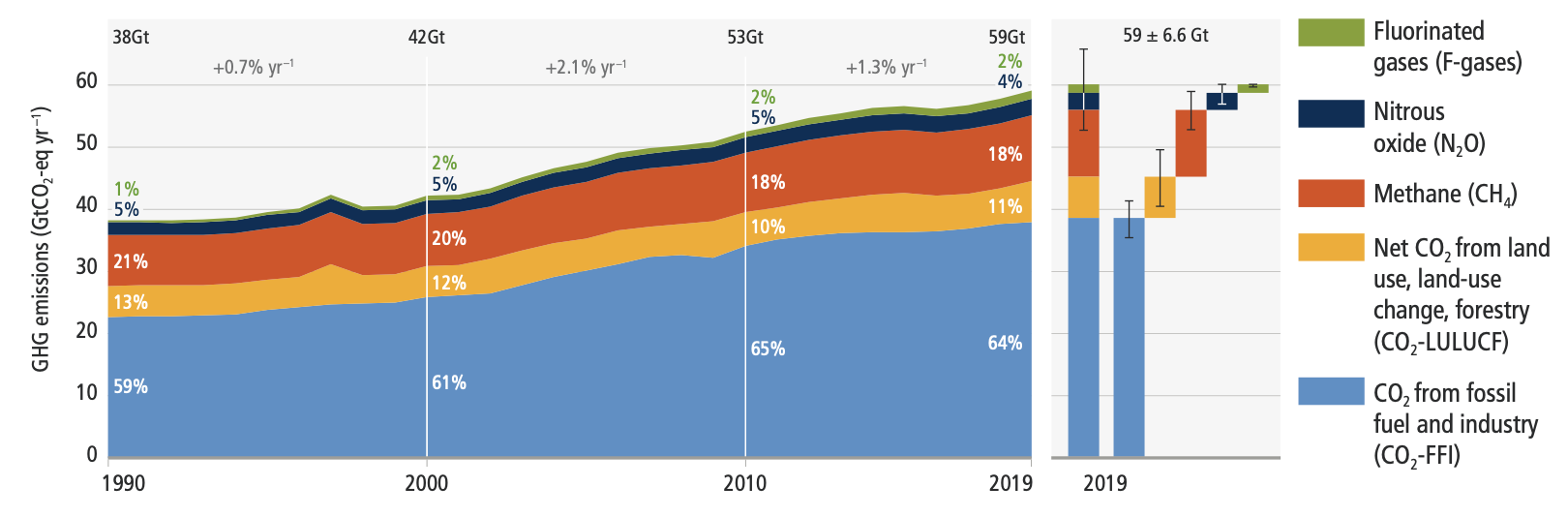

Recent Developments and Current Trends

Total net anthropogenic GHG emissions6 have continued to rise during the period 2010–2019, as have cumulative net CO2 emissions since 1850. Regional contributions to global GHG emissions continue to differ widely. Variations in regional, and national per capita emissions partly reflect different development stages, but they also vary widely at similar income levels. The 10% of households with the highest per capita emissions contribute a disproportionately large share of global household GHG emissions. At least 18 countries have sustained GHG emission reductions for longer than 10 years.

Globally, the 10% of households with the highest per capita emissions contribute 34–45% of global consumption-based household GHG emissions,21 while the middle 40% contribute 40–53%, and the bottom 50% contribute 13–15%.

The unit costs of several low-emission technologies have fallen continuously since 2010. Innovation policy packages have enabled these cost reductions and supported global adoption.

There has been a consistent expansion of policies and laws addressing mitigation since AR5. This has led to the avoidance of emissions that would otherwise have occurred and increased investment in low-GHG technologies and infrastructure. Policy coverage of emissions is uneven across sectors.

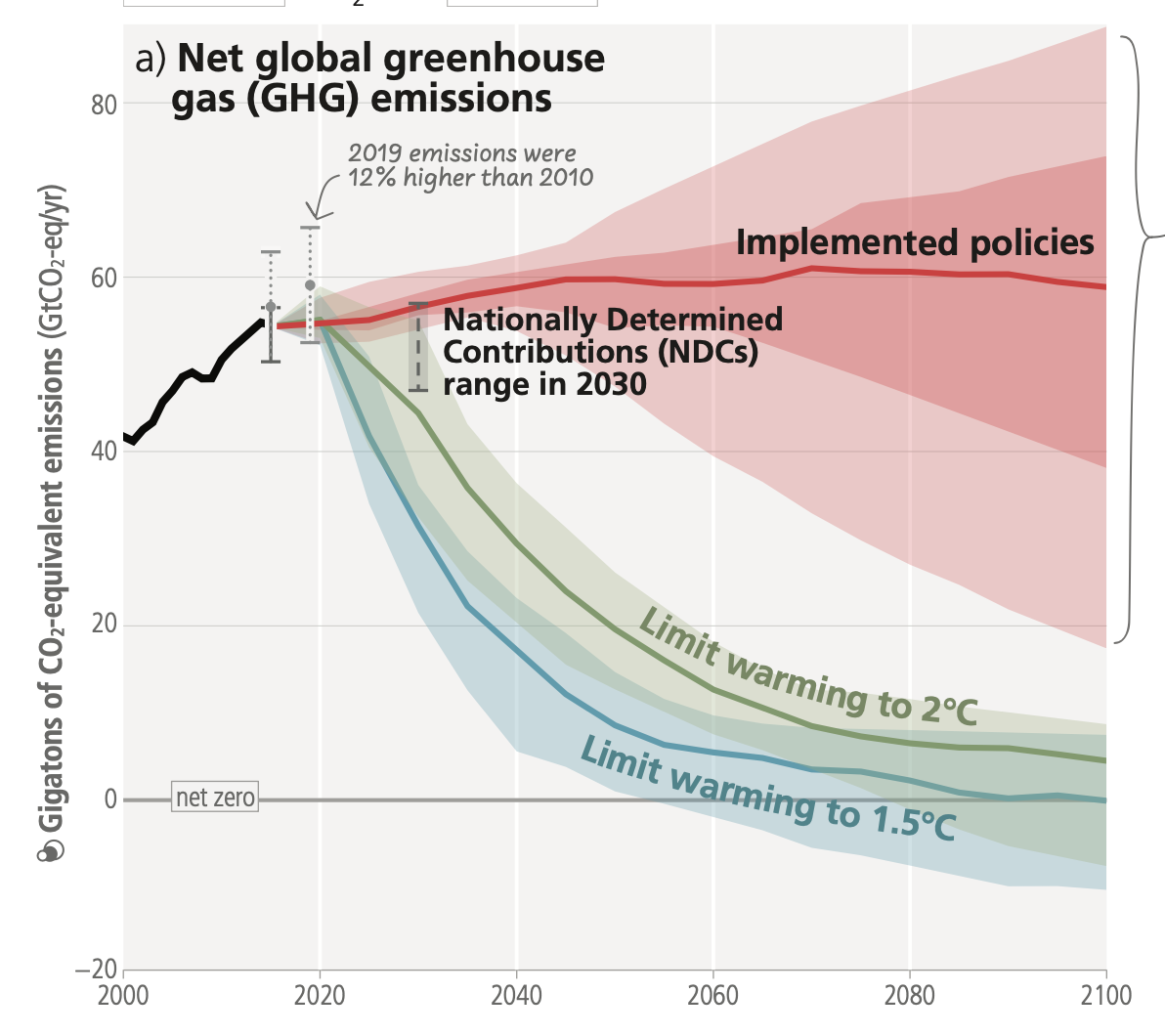

Global GHG emissions in 2030 associated with the implementation of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) announced prior to COP2623 would make it likely that warming will exceed 1.5°C during the 21st century.24 Likely limiting warming to below 2°C would then rely on a rapid acceleration of mitigation efforts after 2030.

System Transformations to Limit Global Warming

Global GHG emissions are projected to peak between 2020 and at the latest before 2025 in global modelled pathways that limit warming to 1.5°C (>50%) with no or limited overshoot and in those that limit warming to 2°C (>67%) and assume immediate action. Without a strengthening of policies beyond those that are implemented by the end of 2020, GHG emissions are projected to rise beyond 2025, leading to a median global warming of 3.2°C by 2100.

All global modelled pathways that limit warming to 1.5°C (>50%) with no or limited overshoot, and those that limit warming to 2°C (>67%), involve rapid and deep and in most cases immediate GHG emission reductions in all sectors.

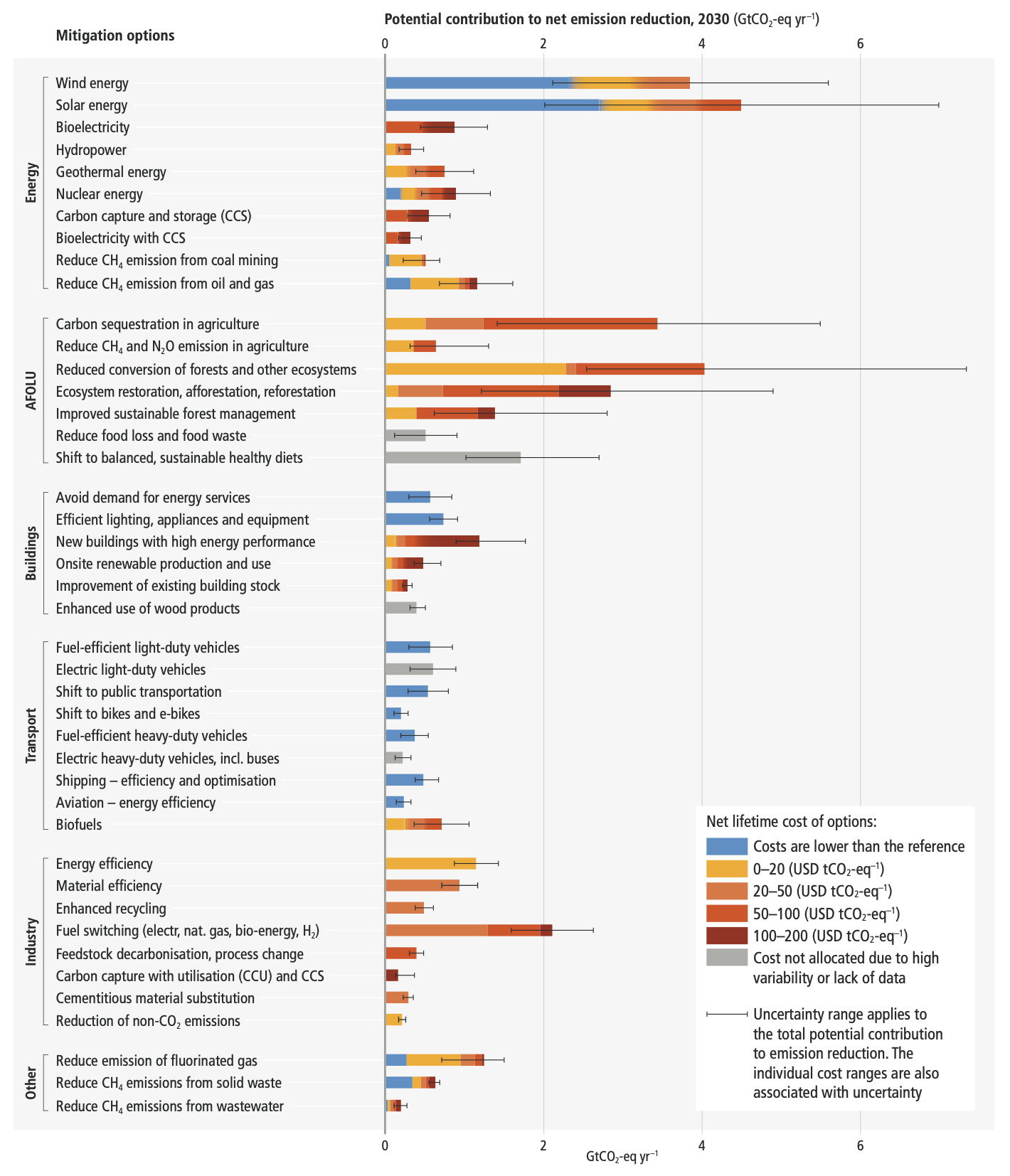

This would involve very low or zero-carbon energy sources, such as renewables or fossil fuels with CCS, demand side measures and improving efficiency, reducing non-CO2 emissions, and deploying carbon dioxide removal (CDR) methods to counterbalance residual GHG emissions.

Reducing GHG emissions across the full energy sector requires major transitions, including a substantial reduction in overall fossil fuel use, the deployment of low-emission energy sources, switching to alternative energy carriers, and energy efficiency and conservation.

Net zero CO2 emissions from the industrial sector are challenging but possible. Reducing industry emissions will entail coordinated action throughout value chains to promote all mitigation options, including demand management, energy and materials efficiency, circular material flows, as well as abatement technologies and transformational changes in production processes.

Urban areas can create opportunities to increase resource efficiency and significantly reduce GHG emissions through the systemic transition of infrastructure and urban form through low-emission development pathways towards net-zero emissions.

In modelled global scenarios, existing buildings, if retrofitted, and buildings yet to be built, are projected to approach net zero GHG emissions in 2050 if policy packages, which combine ambitious sufficiency, efficiency, and renewable energy measures, are effectively implemented and barriers to decarbonisation are removed.

The deployment of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) to counterbalance hard-to-abate residual emissions is unavoidable if net zero CO2 or GHG emissions are to be achieved. The scale and timing of deployment will depend on the trajectories of gross emission reductions in different sectors.

Mitigation options costing USD100 tCO2-eq–1 or less could reduce global GHG emissions by at least half the 2019 level by 2030.

IPCC Assessment Report 6

Introduction

Assessment Report (AR6) summarises the state of knowledge of climate change, its widespread impacts and risks, and climate change mitigation and adaptation. It integrates the main findings of the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) based on contributions from the three Working Groups

Current Status and Trends

Human activities, principally through emissions of greenhouse gases, have unequivocally caused global warming, with global surface temperature reaching 1.1°C above 1850-1900 in 2011-2020. The likely range of total human-caused global surface temperature increase from 1850–1900 to 2010–20197 is 0.8°C to 1.3°C, with a best estimate of 1.07°C.

Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere have occurred. Human-caused climate change is already affecting many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe. This has led to widespread adverse impacts and related losses and damages to nature and people. Vulnerable communities who have historically contributed the least to current climate change are disproportionately affected.

Approximately 3.3 to 3.6 billion people live in contexts that are highly vulnerable to climate change. Human and ecosystem vulnerability are interdependent. Regions and people with considerable development constraints have high vulnerability to climatic hazards.

Impacts on some ecosystems are approaching irreversibility such as the impacts of hydrological changes resulting from the retreat of glaciers, or the changes in some mountain and Arctic ecosystems driven by permafrost thaw.

Climate change has reduced food security and affected water security, hindering efforts to meet Sustainable Development Goals. In all regions increases in extreme heat events have resulted in human mortality and morbidity. The occurrence of climate-related food-borne and water-borne diseases and the incidence of vector-borne diseases have increased. In assessed regions, some mental health challenges are associated with increasing temperatures.

Adaptation planning and implementation has progressed across all sectors and regions, with documented benefits and varying effectiveness. Despite progress, adaptation gaps exist, and will continue to grow at current rates of implementation.

Growing public and political awareness of climate impacts and risks has resulted in at least 170 countries and many cities including adaptation in their climate policies and planning processes. Maladaptation especially affects marginalised and vulnerable groups adversely. Key barriers to adaptation are limited resources, lack of private sector and citizen engagement, insufficient mobilization of finance (including for research), low climate literacy, lack of political commitment, limited research and/or slow and low uptake of adaptation science, and low sense of urgency.

Policies and laws addressing mitigation have consistently expanded since AR5. Global GHG emissions in 2030 implied by nationally determined contributions (NDCs) announced by October 2021 make it likely that warming will exceed 1.5°C during the 21st century and make it harder to limit warming below 2°C. There are gaps between projected emissions from implemented policies and those from NDCs and finance flows fall short of the levels needed to meet climate goals across all sectors and regions.

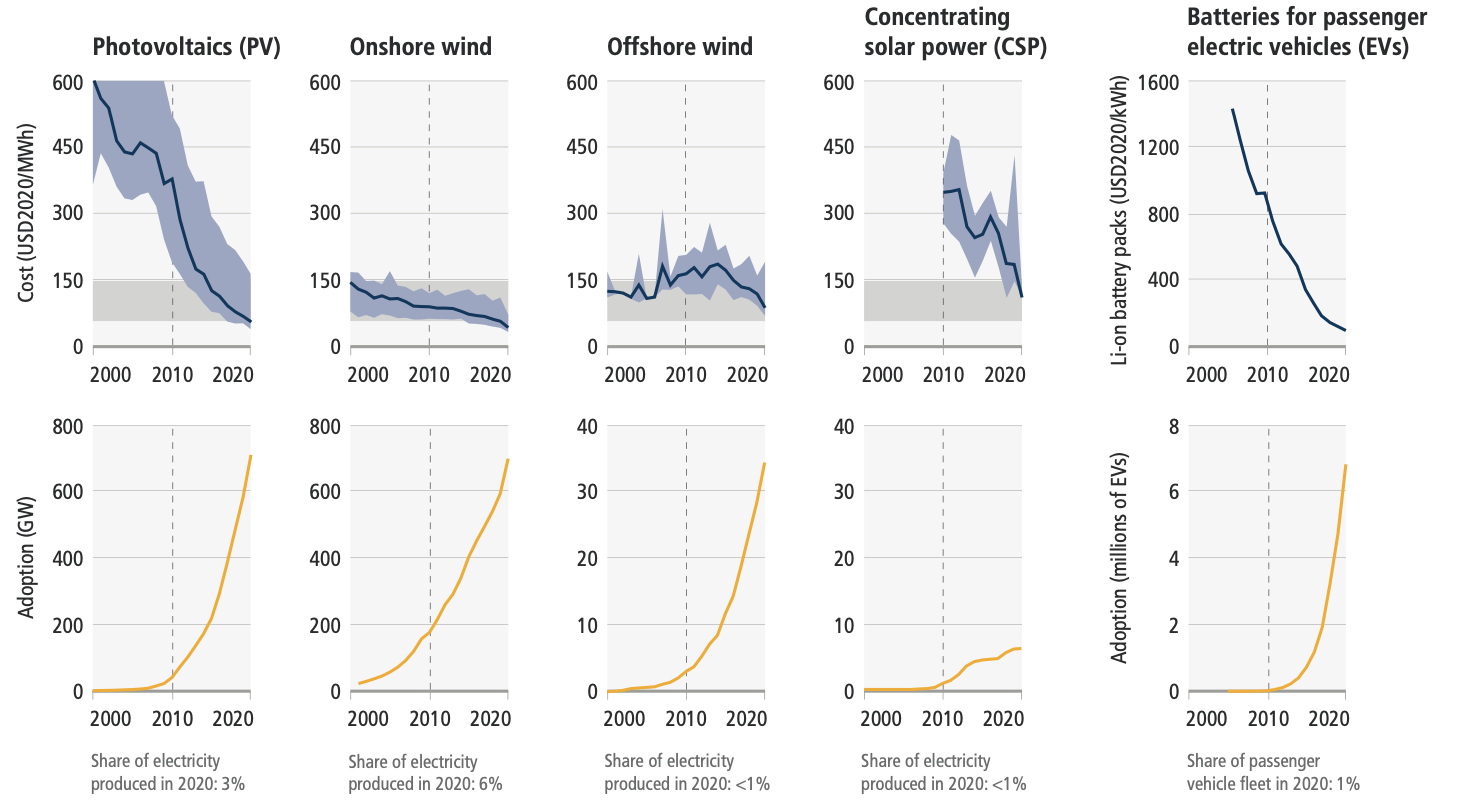

From 2010 to 2019 there have been sustained decreases in the unit costs of solar energy (85%), wind energy (55%), and lithium-ion batteries (85%), and large increases in their deployment.

Policies implemented by the end of 2020 are projected to result in higher global GHG emissions in 2030 than emissions implied by NDCs, indicating an ‘implementation gap’.

Future Climate Change, Risks, and Long-Term Responses

Continued greenhouse gas emissions will lead to increasing global warming, with the best estimate of reaching 1.5°C in the near term in considered scenarios and modelled pathways. Every increment of global warming will intensify multiple and concurrent hazards.

Global warming will continue to increase in the near term (2021–2040) mainly due to increased cumulative CO2 emissions in nearly all considered scenarios and modelled pathways. In the near term, global warming is more likely than not to reach 1.5°C even under the very low GHG emission scenario and likely or very likely to exceed 1.5°C under higher emissions scenarios.

With further warming, every region is projected to increasingly experience concurrent and multiple changes in climatic impact-drivers. Compound heatwaves and droughts are projected to become more frequent, including concurrent events across multiple locations. Projected regional changes include intensification of tropical cyclones and/or extratropical storms, and increases in aridity and fire weather.

With every increment of global warming, regional changes in mean climate and extremes become more widespread and pronounced. Risks and projected adverse impacts and related losses and damages from climate change escalate with every increment of global warming. The level of risk will also depend on trends in vulnerability and exposure of humans and ecosystems. Future exposure to climatic hazards is increasing globally due to socio-economic development trends including migration, growing inequality and urbanisation.

Some future changes are unavoidable and/or irreversible but can be limited by deep, rapid, and sustained global greenhouse gas emissions reduction. The likelihood of abrupt and/or irreversible changes increases with higher global warming levels. Deep, rapid, and sustained GHG emissions reductions would limit further sea level rise acceleration and projected long-term sea level rise commitment.

As warming levels increase, so do the risks of species extinction or irreversible loss of biodiversity in ecosystems including forests, coral reefs, and in Arctic regions.

Adaptation options that are feasible and effective today will become constrained and less effective with increasing global warming. With increasing global warming, losses and damages will increase and additional human and natural systems will reach adaptation limits.

Limiting human-caused global warming requires net zero CO2 emissions. Cumulative carbon emissions until the time of reaching net zero CO2 emissions and the level of greenhouse gas emission reductions this decade largely determine whether warming can be limited to 1.5°C or 2°C. All global modelled pathways that limit warming to 1.5°C (>50%) with no or limited overshoot, and those that limit warming to 2°C (>67%), involve rapid and deep and, in most cases, immediate greenhouse gas emissions reductions in all sectors this decade.

If warming exceeds a specified level such as 1.5°C, it could gradually be reduced again by achieving and sustaining net negative global CO2 emissions. This would require additional deployment of carbon dioxide removal, compared to pathways without overshoot, leading to greater feasibility and sustainability concerns. Overshoot entails adverse impacts, some irreversible, and additional risks for human and natural systems, all growing with the magnitude and duration of overshoot.

Responses in the Near Term

There is a rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all. increased international cooperation including improved access to adequate financial resources, particularly for vulnerable regions, sectors and groups, and inclusive governance and coordinated policies.

Deep, rapid, and sustained mitigation and accelerated implementation of adaptation actions in this decade would reduce projected losses and damages for humans and ecosystems. Delayed mitigation and adaptation action would lock in high-emissions infrastructure, raise risks of stranded assets and cost-escalation, reduce feasibility, and increase losses and damages. Near-term actions involve high up-front investments and potentially disruptive changes that can be lessened by a range of enabling policies.

These system transitions involve a significant upscaling of a wide portfolio of mitigation and adaptation options. Feasible, effective, and low-cost options for mitigation and adaptation are already available, with differences across systems and regions.

Prioritising equity, climate justice, social justice, inclusion and just transition processes can enable adaptation and ambitious mitigation actions and climate resilient development. Adaptation outcomes are enhanced by increased support to regions and people with the highest vulnerability to climatic hazards.

ACE: A fast, skillful learned global atmospheric model for climate prediction

ACE is a global atmospheric model that uses a neural network to learn the dynamics of the atmosphere.

- 200M parameters auto-regressive model

- 100 km resolution global atmospheric model

- 6 hours temporal resolution, stable for 100 years

Model

The architecture uses a Spherical Fourier Neural Transformer (SFNT) to learn the dynamics of the atmosphere. This model uses a spherical harmonic transform of the grid, which is more suitable for the spherical geometry of the Earth. This enables more efficient computation of convolutions on spherical space.

The dataset used is FV3GFS, which is a global atmospheric model with 100 km resolution used as the US weather model.

As normalization of samples, residual scaling is used. Where predicting an output always equal to the input for each variable would mean that each variable contributes equally to the loss (indipendently of the scale of variables).

Experimental Transformer

ExPT is a transformer architecture that uses unsupervised learning and in-context pretraining (few-shot training in Transformers).

- Pretraining: unlabeled designs from context X (without score). Using synthetic data, so functions that operate on the same domain as the objective function.

- Fine-tuning (Adaptation): the model conditions using a small amount of pairs <design, score>

How do we generate the functions? -> there are several ways (ex. Gaussian Mixtures, Gaussian Processes, etc.) In this case Gaussian Processes are used with RBF kernels.

Model

Encoder model is used for pairs \(<\texttt{design}, \texttt{score}>\), in conjunction with y_m, to create an hidden vector h. Token embedding is done with two linear layers, one for the pairs and one for the score.

How do we model conditional probability? -> we use a Variational Auto-Encoder to model the conditional probability \( p_{\theta}(x_i | h_i) \).

Closed-form continuous-time neural networks

Introduction

Closed-form continuous-time (CfC) models resolve the bottleneck of liquid networks (requiring a differential equation solver, which lengthens the inference and training time) by approximating the closed-form solution of the differential equation.

Approximating Differential Equations

We need to derive an approximate closed-form solution for LTC networks.

\( x(t) = B \dot e−[wτ + f(x,I;θ)]t \dot f(−x, −I; θ) + A \)

The exponential term in the equation drives the system’s first part (exponentially fast) to 0 and the entire hidden state to A. This issue becomes more apparent when there are recurrent connections and causes vanishing gradient factors when trained by gradient descent.

To reduce this effect, we replace the exponential decay term with a reversed sigmoidal nonlinearity.

The bias parameter B is decided to be part of the trainable parameters of the neural network and choose to use a new network instance instead of f (Bias).

We also replace A with another neural network instance, h(. ) to enhance the flexibility of the model.

Instead of learning all three neural network instances f, g and h separately, we have them share the first few layers in the form of a backbone that branches out into these three functions. As a result, the backbone allows our model to learn shared representations.

The time complexity of the algorithm is equivalent to that of discretized recurrent networks, being at least one order of magnitude faster than ODE-based networks.

Problems

CfCs might express vanishing gradient problems. To avoid this, for tasks that require long-term dependences, it is better to use them together with mixed memory networks.

Inferring causality from ODE-based networks might be more straightforward than a closed-form solution.

Recurrent Fast Weight Programmers

Introduction

With linear transformers, we can prove FWP are effective and fast. In this case both slow and fast networks are Feed Forward Networks, and consist of the same layer.

What if we add recurrence to slow and fast networks?

Delta RNN

Use RNN for fast weights.

Add recurrent term to feedforward of linear transformer.

\( y^{(t)} = W^{(t)}q^{(t)} + R^{(t)}f(y^{(t-1)}) \)

where \( R^{(t)} \) is the recurrent matrix with additional fast weights, and \( f(y^{(t-1)}) \) is the output of fast net at previous time step + softmax activation function.

Recurrent Delta RNN

Make also slow network recurrent via the fast network, taking fast network previous output as input.

\( k^t = W_kx^t + R_k f(y^{t-1}) \) \( v^t = W_vx^t + R_v f(y^{t-1}) \) \( q^t = W_qx^t + R_q f(y^{t-1}) \)

where \( R_k, R_v, R_q \) are the recurrent matrices for the slow network (slow weights), and each equation corresponds to query, key and value pairs calculations for attention of the slow network.

Problems

The network causes additional complexity with regards to linear transformers, but it is still linear (same order of complexity).

Liquid Neural Networks

Introduction

In classical statistics there is an optimal amount of paramterers for a model, after which performance decreases. This problem is known as overparametrization and is also present in neural networks. The recent developments in transformers and vision transformers have shown that overparametrization can be beneficial for performance.

Benefits include new emergent behaviours, more general learning and better generalization and robustness. This is at the cost of increased computational complexity and memory requirements, as well as lower accuracy on minority samples.

Brain inspired, building blocks are neurons and equations from neuron to neuron.

Characteristics

Liquid neural networks stay adaptable even after training. Good for going out of distribution, so for real world applications (drone navigation, self driving cars).

Neural dynamics are continuous processes, so they can be described by differential equations.

Liquid State Machines

Continuous time/depth neural networks (CTRNNs) are a type of recurrent neural network (RNN) where the nodes (neurons) are described by differential equations.

\( \frac{dx(t)}{dx} = f_{n,k,l}(x(t), I(t), \theta) \)

Where f is the neural network, x is the state of the neuron, I is the input and \(\theta\) are the parameters of the network.

The state of the network is the state of all the neurons in the network.

There is no computation for each time step, the network is updated arbitrairly, unlike RNNs.

\( \frac{dx(t)}{dx} = -\frac{x(t)}{\tau} + f_{n,k,l}(x(t), I(t), \theta) \)

Implementation

We need a numerical ODE solver, to resolve the differential equations.

The backward pass can either be done with the adjoint sensitivity method (loss + neural ODE solver + adjoint state) or with the backpropagation through time method (classic). The latter method is considered better as it is not a black box.

Liquid Time-Constant Networks

Leaky integrator neural model

\( \frac{dx(t)}{dt} = -\frac{x(t)}{\tau} + f_{n,k,l}(x(t), I(t), \theta) \)

Uses conductance-based synapses, which are more biologically plausible than the classic synapses.

\( S(t) = f_{n,k,l}(x(t), I(t), \theta)(A - x(t)) \)

\( \frac{dx(t)}{dt} = - [\frac{1}{\tau} + f_{n,k,l}(x(t), I(t), \theta)]x(t) + f_{n,k,l}(x(t), I(t), \theta)A \)

The first term is time-dependent, while the second term the input representation at the current time step.

Activations are changed to differential equations, interactions are given by non-linearity (ex. neural nets).

The network might associate the dynamics of the task with its own behaviour (ex. steering left/right implies camera movement).

The liquid time-constant (LTC) model is based on neurons in the form of differential equations interconnected via sigmoidal synapses.

Because LTCs are ordinary differential equations, their behavior can only be described over time. LTCs are universal approximators and implement causal dynamical models. However, the LTC model has one major disadvantage: to compute their output, we need a numerical differential equation-solver which seriously slows down their training and inference time.

Expressivity

Using the trajectory length method it is possible to measure the expressivity of a network. The method consists in projecting the latent space of the network onto a lower dimensional space and measuring the length of the trajectory in the lower dimensional space (ex. 2D).

These networks tend to have a higher expressivity than RNNs, but are bad with long term dependencies.

Differential equations can form causal structures, which is good.

Some limitations include:

- the complexity of this network is tied to the ODE solver, which use fixed steps. Some solutions include Hypersolvers, closed form solutions and sparse flows.

- Vanishing gradients and exploding gradients are still a problem. A possible solution is to use a mixed memory wrapper.

Neural Circuit Policies

Neural Circuit Policies are recurrent neural network models inspired by the nervous system of the nematode C. elegans. Compared to standard ML models, NCPs have

- Neurons that are modeled by an ordinary differential equation

- A sparse structured wiring

Liquid Structured State Space Models

Introduction

Linear state space models have been used succesfully to learn representation of sequential data.

In this approach, the structured state space model (S4) is combined with LTC space model to include the input dependant state-transition module. The liquid kernel structure takes into account the similarity between samples in sequences at train and inference time.

Continuous-time state space model

\( \hat{x}(t) = Ax(t) + Bu(t) \) \( y(t) = Cx(t) + Du(t) \)

where \( u(t) \) is a 1d input signal, \( x(t) \) is the hidden state vector, \( y(t) \) is the output vector, and A, B, C, D are the system parameters.

The previous model can then be discretized using the Euler method:

\( x_k = \hat{A}x_{k-1} + \hat{B}u_{k} \) \( y_k = Cx_k \)

where \( \Delta t \) is the time step, and D is equal to zero.

And convolution can be applied to speed up the computation: